A Non-Mathematician's Apology

This intellectual rush once fueled humanity’s technological progress; it just happens to be unconnected to any real application here. It’s like our evolved love for fatty foods, which has become unhealthy in the era of fried snacks.

2023-8-18

Noble Pursuits

“Don’t you envy mathematicians?”

“Excuse me?” My advisor, a cryptographer, looked at me, puzzled.

We were debating whether I should drop my abstract algebra course. The class was eating up too much of my time, and I wasn’t excelling in it. But abstract algebra is a gateway to “real” math, so I was reluctant to give up the chance to explore this supposedly “purer” form of mathematics.

I tried to awaken his intellectual conscience.

“Isn’t math more fundamental, deeper, more noble? Doesn’t it train the mind in a way that no other subject can match?”

“I don’t think learning math sharpens the mind any more than learning cryptography does.”

So I tried a different angle, one I’d heard from my parents:

“Isn’t that why companies like Citadel and Jane Street prefer to hire math and physics majors over finance majors? Math and physics bring a deeper understanding to finance than studying finance directly.”

“Huh? I think it’s just that there are way too many physics PhDs competing for faculty positions, so they go to quant finance instead. Who’s to say they wouldn’t have done just as well in finance if they’d studied it directly?”

I was still reluctant:

“But isn’t math something you can only really study in college? If I don’t learn it now, won’t it be tough if I need it later? Like, don’t you need abstract algebra in cryptography?”

“I never took abstract algebra in college. And the parts you need for cryptography are just small slices you can pick up from papers.”

Then he switched to another argument.

“Besides, you didn’t take abstract algebra as a prerequisite for anything else. You chose it for fun. If you’re not having fun, you should just drop it.”

It seemed like my advisor and I viewed math differently. To him, math was just another intellectual hobby, a plaything you could play with if it amused you and set aside if it didn’t.

But I had more romantic ideas about math. Especially about pure math, which abstract algebra represents, and which Hardy in A Mathematician’s Apology saw as the most beautiful part of mathematics. Galois laid the foundations of abstract algebra in prison and then died in a duel over love at just 20 years old—my age. Pure math is supposedly the field most expressive of human intellectual ambition. Dropping this course felt like abandoning the pursuit of truth and beauty. How could I face the great intellectual traditions of the past?

In the end, I dropped the course.

This is my non-mathematician’s apology.

Practicality

The first step in reconciling myself with this decision was realizing that math isn’t as “useful” as I’d thought. Perhaps this belief comes from my Asian parents. I suspect many parents, even if they aren’t science-minded, push their kids to learn math with this view in mind.

In some ways, this is true; math is useful for STEM students through high school and freshman year. But for those who truly love math, the math they study isn’t all that practical, and the more advanced it is, the less useful it tends to be. Math development outpaces its applications by at least a century.

So why do they study it? Mainly for the intellectual thrill of coming up with proofs.

This thrill is not unlike the pleasure of finding a winning strategy in a game; some people even see no difference between the two.

For instance, when a close friend was applying to college, he asked if he should list his achievement of climbing to the top of the Hearthstone ladder as an accomplishment.

“Uh, what?”

“Oh, I didn’t actually reach the top. I mean, I did once, but that was just because I was stream-sniping a popular player, so it doesn’t count. My real high rank was ninth.”

“No, what I meant was, I just don’t think admissions officers would take that seriously.”

“Well, people list their math competition and chess ranks. Why not ladder ranks in Hearthstone?”

I couldn’t find a counter-argument. I had to admit my friend’s mathematical foundation was solid and that he had a sharp, unique sense of aesthetics. Hardy also believed that the difference between games and math is mostly a matter of intensity:

“A chess problem is simply an exercise in pure mathematics . and everyone who calls a problem ‘beautiful’ is applauding mathematical beauty, even if it is a beauty of a comparatively lowly kind. We may learn the same lesson, at a lower level but for a wider public, from bridge, or descending farther, from the puzzle columns of the popular newspapers. Nearly all their immense popularity is a tribute to the drawing power of rudimentary mathematics, and the better makers of puzzles use very little else. They know their business: what the public wants is a little intellectual ‘kick’, and nothing else has quite the kick of mathematics. ”

Yes, math and games differ mainly in difficulty, which is why math gives a stronger “kick.” Those who can’t enjoy advanced math can still appreciate the beauty of logic through games, a kind of “diluted math.” If games are like digital heroin, then math is like rational heroin.

Hardy nailed it. Many around me who love learning are somewhat addicted to problem-solving. For some former competitive programmers, competition problems are so thrilling that they’ve given up computer games altogether—just as Sherlock Holmes only stayed off drugs when he had cases to solve. Problems were more stimulating than games.

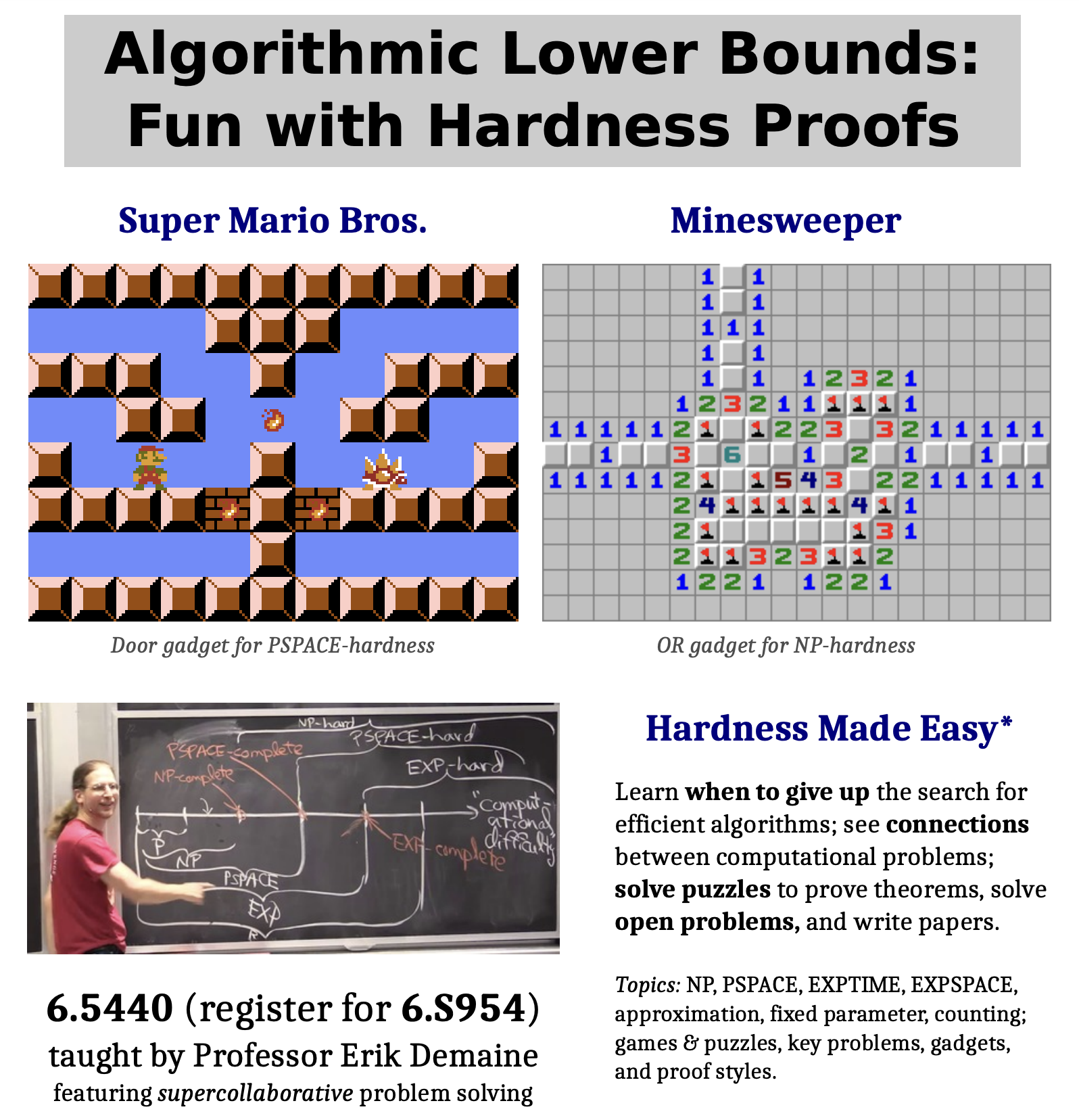

Of course, problems and games aren’t mutually exclusive. This semester, I dropped another course called “Fun with Hardness,” a theoretical computer science course that could be considered a form of math. The professor, a genius who earned his PhD at 20, cheerfully proved which computer games couldn’t be solved in polynomial time. This week it was Super Mario speedruns, next week Tetris with thirteen-square pieces.

Every year, papers come out of this class, and my classmates are some of the smartest people I’ve met, their faces alight with enjoyment. But honestly, the class isn’t all that useful. The professor intentionally created algorithm-hostile levels to prove they couldn’t be solved, yet that didn’t prevent AI from finding “good enough” solutions in most cases.

While I enjoyed the intellectual energy, I also felt a twinge of guilt. The world’s brightest minds, gathering here just to indulge in a kind of “rational heroin” that delivered purified intellectual pleasure, free of any real-world application?

I said, “I don’t think I should stay. This class is too useless.”

Alex (flexing): “It makes you strong, you know.”

Strong? For what? If we spend our lives in a gym, building muscle for the sake of building muscle, what do we use it for? To lift heavier weights?

Beauty

Once I understood their real motivation for studying math, I had the courage to say no to “math shaming.” During a visit to a friend at Stanford, I asked if I could sit in on a math class.

He said, “I have complex analysis tomorrow. Want to join?”

“Oh, then never mind.”

He laughed. “So, no math except probability and linear algebra?”

“Yup. Complex analysis? Complete dog shit.”

(Probability and linear algebra are pretty much the only math that computer science students need for jobs.)

Hardy said, “It is undeniable that a good deal of elementary mathematics—and I use the word ‘elementary’ in the sense in which professional mathematicians use it, in which it includes, for example, a fair working knowledge of the differential and integral calculus—has considerable practical utility. These parts of mathematics are, on the whole, rather dull; they are just the parts which have the least aesthetic value. The ‘real’ mathematics of the ‘real’ mathematicians, the mathematics of Fermat and Euler and Gauss and Abel and Riemann, is almost wholly ‘useless’.”

Complex analysis is one of those “real” maths. Math, like a flower vase without flowers, is most beautiful when it’s art for art’s sake.

Hardy quotes Gauss’s view that number theory, by virtue of its supreme uselessness, should be the “queen of mathematics.” He adds that mathematicians, both great and small, should be glad that such a field exists, untouched by “worldly concerns,” preserving its gentleness and purity.

Hardy may have spoken too soon. Number theory, along with abstract algebra—the course I considered dropping—eventually became foundational to modern cryptography, widely applied in defense work during and after World War II.

I wonder if Hardy would have felt that practicality stained number theory, robbing it of its “gentle purity,” rendering it unworthy of his pale, aristocratic hands.

Sometimes, I wonder if I’m too pragmatic. Judging these “high and pure” pursuits by their utility isn’t my place. Science advances because of seemingly useless curiosity. Some theoretical developments can’t reveal their uses immediately because they’re too abstract—and yet, this abstraction brings benefits.

Some people are drawn to math precisely because it strips away the irrelevant details of the material world, allowing us to see straight to the essence. I call Hardy’s side the “Aesthetic Camp” and this side the “Essence Camp.”

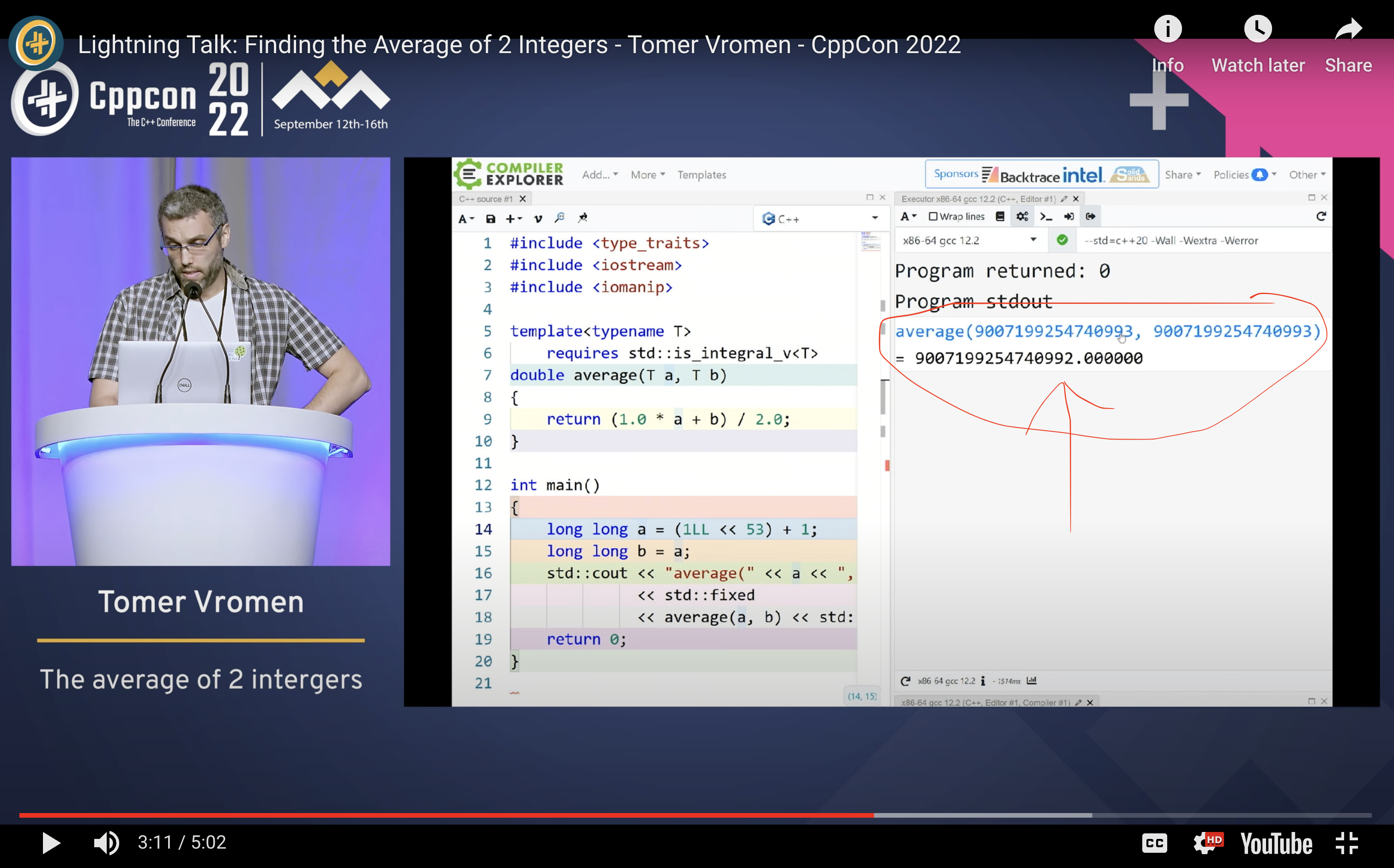

A math major friend once told me he liked math because, for lack of a better word, it felt more “pure” and “essential” than other subjects. He cited a talk he saw on how computers can’t calculate the average of two numbers accurately.

Averages are conceptually simple in math but nearly impossible to calculate accurately in computing. He felt these “dirty details” were strange limitations of our world with no intrinsic meaning.

But to me, that example highlights an important real-world limitation: storing information requires space, and space is finite, so infinite precision is impossible. He might think of an idealized Platonic “average,” but to represent it concretely, limited precision is inevitable—maybe that ideal average is a fantasy, a “spherical chicken in a vacuum.”

I don’t think the material world is “dirty.” To me, it’s essential. I wouldn’t want to claim I’m an intellectual and use the “filth” of the material world as an excuse to be cynical.

The material world isn’t dirty. I admire those who pursue beauty in the world, who blend the lofty with the mundane. I chose computer science because it best embodies the struggle between beauty and practicality. It challenges my pursuit of beauty more than anything else.

Math and art can take their time to reach perfection, existing purely in the mind like polished diamonds. But computers operate in the physical world, and every program has to run within logical and real-world constraints. Programmers make trade-offs between elegance and functionality in finite time. They must embrace human fuzziness; they are the bridge between the concrete and the abstract.

Programs are always works in progress, like cathedrals built from clay—a monument to Platonic ideals crafted from the most constrained materials. Creating beauty from diamonds is easy; creating beauty from clay is the challenge. Computers add a dimension of struggle that math and art do not.

But if ChatGPT develops to the point where studying computer science loses its purpose, what would I do?

I could hold onto the “beauty” of computer science like an old-timer stuck in the past, but once it loses its usefulness, it would become another plaything like art or math—a fan to be shredded like a prop in Dream of the Red Chamber, stripped of that tension between utility and elegance.

It would be like dancing to a song that’s already ended, clinging to the beat of a previous tune in the corner of the room. You could call it staying true to oneself, or you could call it stubbornness.

Fuzzy Feelings

“If you ask DeepMind or OpenAI, they might say that my pursuit of ‘science’ or ‘explainability’ is really just about seeking that fuzzy feeling of intellectual satisfaction…” — a classical ML professor

One day while studying with a friend, I noticed she was struggling with some challenging probability problems, so I mentioned a basic question. She didn’t know how to answer it.

“If six classes are hard for you, wouldn’t four classes be a more productive balance?”

“But I feel like I’m getting smarter by pushing my limits. Look at the hard stuff I’m learning! It’s way more complex than what I used to learn.”

“If you’re taking on harder topics but not really absorbing them, then aren’t you just left with a false sense of progress? Is your goal real knowledge, or just that fuzzy feeling that you’re learning?”

“I can just brush up on it later. Aren’t we all monkeys with electrodes, living in a bubble driven by dopamine?”

Exactly. Whether it’s my fixation on beauty or a mathematician’s obsession with truth, in the end, it’s all about pursuing a “fuzzy feeling.”

Even if we rationalize it later as the pursuit of beauty, truth, or essence, it starts with that thrill of mastery. Without that satisfaction, just talking about “beauty” or “truth” wouldn’t be enough to convince anyone.

In hindsight, maybe I should have stayed in “Fun with Hardness.” Rather than treating it as a practical course, I could have viewed it as a course in art history, an introduction to aesthetics. Although our goals were different, I wouldn’t have wanted to miss out on sharing that intellectual rush with them. This intellectual rush once fueled humanity’s technological progress; it just happens to be unconnected to any real application here. It’s like our evolved love for fatty foods, which has become unhealthy in the era of fried snacks.

So, why didn’t I study math?

Maybe I just enjoy this material world too much.

(Also, maybe because I’m not very good at math…)