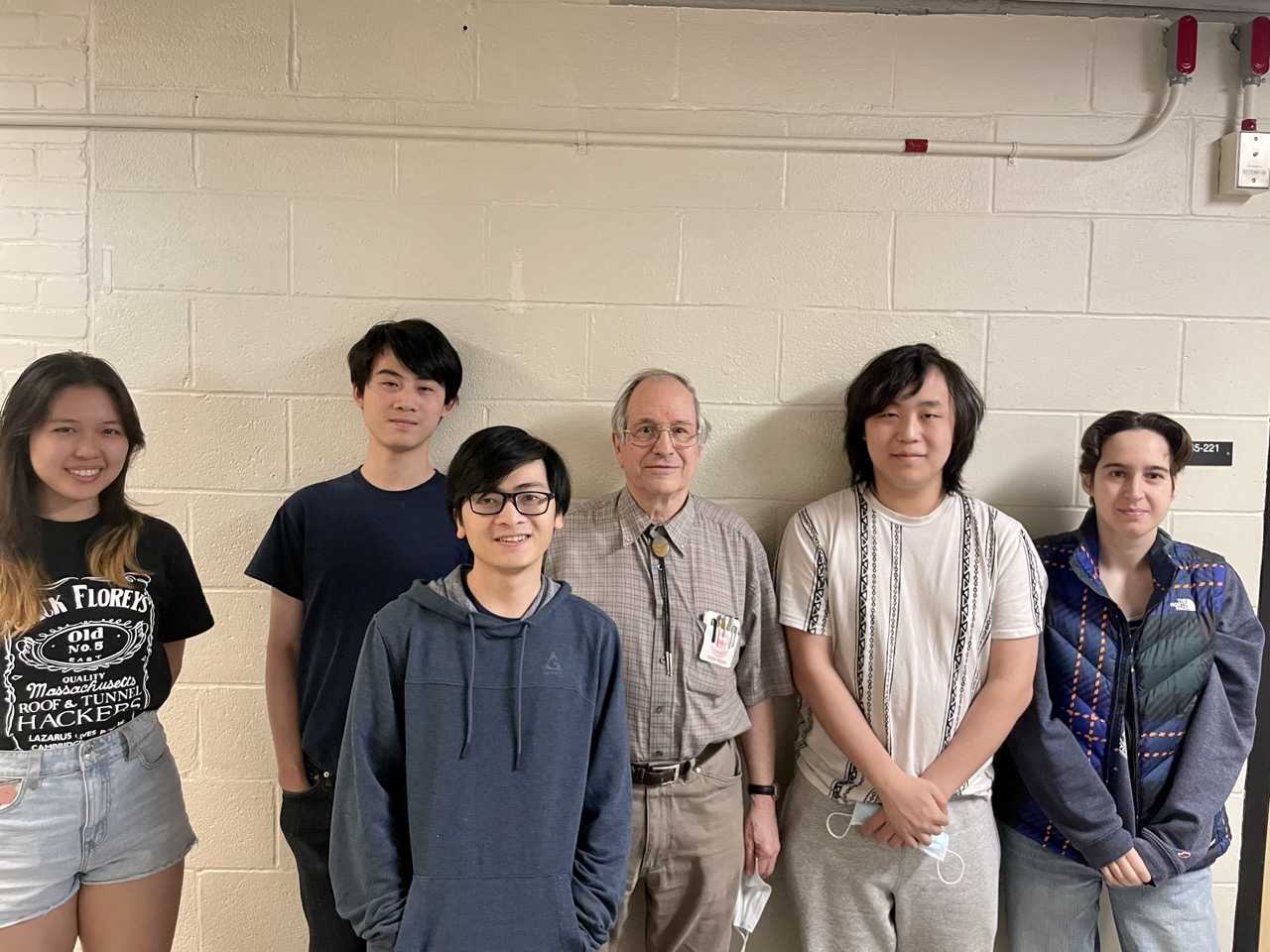

Old Guy Sussman

He wanted to spend his life programming in Scheme. He did just that. He seems happy.

2023-5-15

Part One

Back when we programmers debugged over the phone…

“Rumor has it, this old guy is tough.”

“Yes, he does as he pleases… No recording, no slides, no regular office hours. I heard the department lets him teach this course just because he’s Sussman.”

Fortunately, the old guy doesn’t understand our whisperings in Chinese. He calmly pulled a stack of documents from his briefcase and laid them on the desk, clipped the microphone to his “Nerd Pride” shirt, prominently displaying several pencils in his shirt pocket. This was my first impression of the old guy.

Gerald Jay Sussman, 76, a professor in the MIT EECS Department, inventor of the Scheme programming language, author of “Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs (SICP)” and “Software Development for Flexibility (SDF),” both classics in the CS curriculum. If we compare Python to English, then Scheme would be Latin: deeply influential and clearly structured, yet archaic and seldom used.

Of course, I only learned these things later. My reason for choosing the Large Symbolic Systems (6.905/6.945) programming class was simply because I heard from an upperclassman that Sussman liked to chat over tea with students. However, when I talked to friends about wanting to take this class, all I heard is negative comments. Some said he was inflexible, others complained he often went off-topic during Circuit recitations, and some hesitated before concluding, “Well… he is strongly-opinionated for sure.” I figured the only way to know if the course was right for me was to enroll.

“Today we’re talking about the Scheme programming language. Any programming language, whether it’s Python, Java, or Lisp, is composed of only three parts: primitives, means of combination, and means of abstraction…”

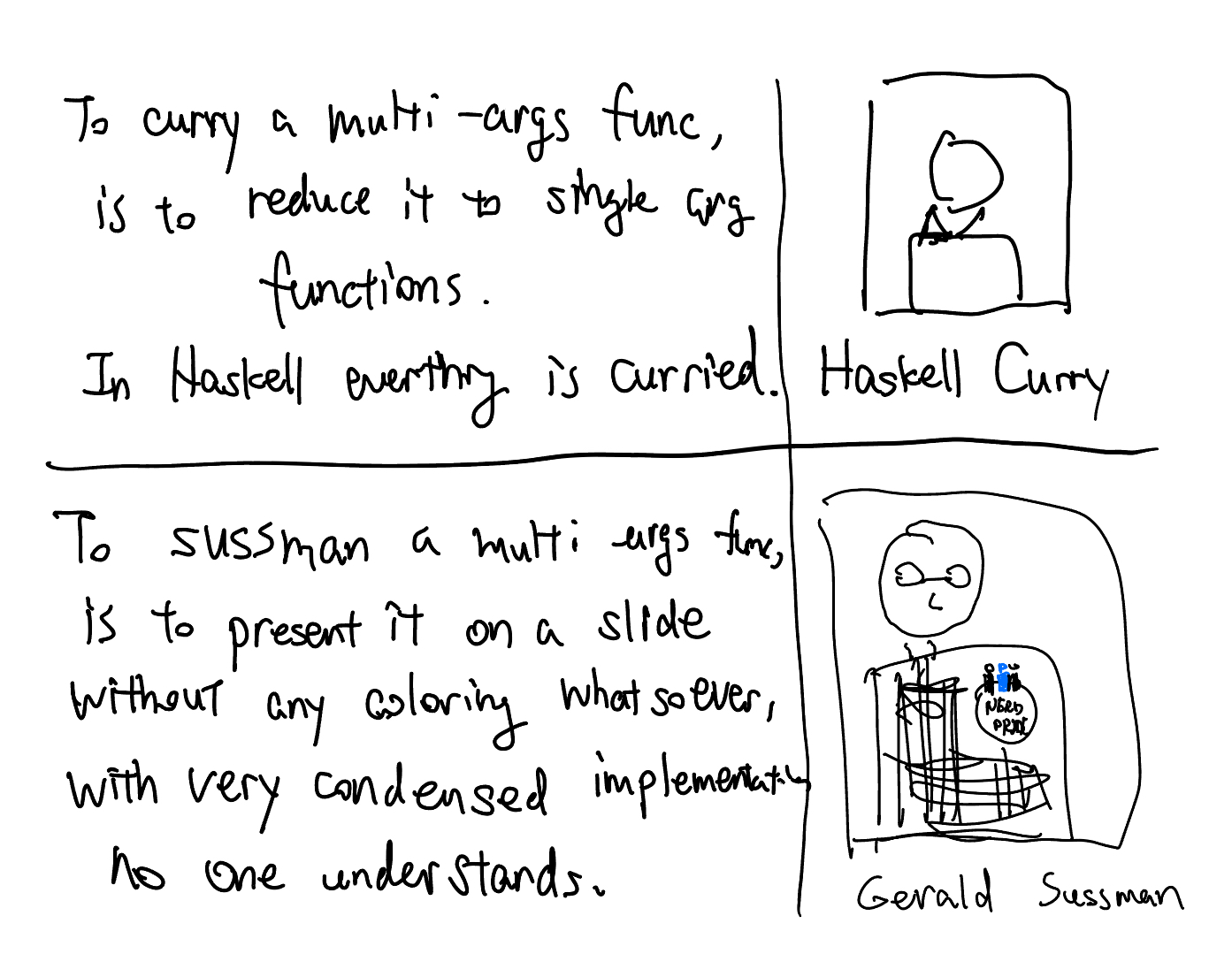

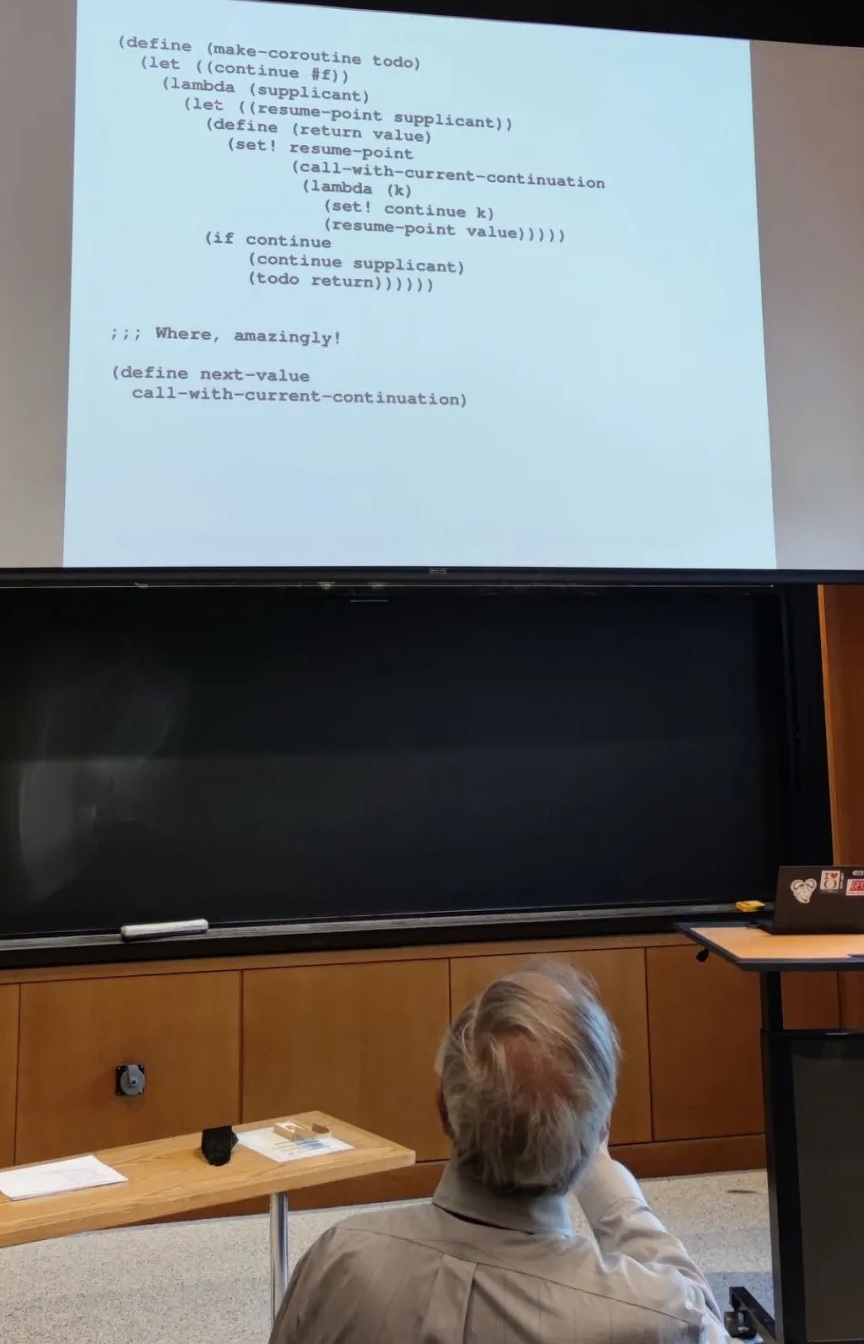

He flipped through the slides one by one; the presentation contained only code, no English. He explained from the first line to the last, then flipped to the next page, repeat. As he spoke, he reminisced about the old days, like “back when we programmers debugged over the phone,” “when I was writing Fortran on the XX-XX machine at IBM,” and “the night in the ’70s when my buddy Guy Steele and I wrote the first Scheme interpreter…” When class ended, he declared, “Alright, that is the entirety of the Scheme language. Since I have shared everything this time, I won’t teach it again. Class dismissed.”

Part Two

Afterward, every class felt like it was on 1.5x speed, with the old guy explaining the code from the first line to the last. This was his language, one he had been writing for nearly 50 years; he could read Scheme faster than I could read English. Once he had finished all the slides, he would look at his watch, chuckle, and say, “Haha, I finished five minutes early again today,” leaving a group of students completely baffled. After a few classes, the once bustling lecture hall dwindled to just a dozen students. He proudly announced, “This is the ideal class size I’ve always wanted.” With each class, I understood less and less, and I had to do something.

I began interrupting him whenever I didn’t understand something. “Question!” “Yes, sir!” “You argue that this is a better design. But I think…” I’m usually not interested in technical details. What interests me is why a design is good, what innovation it brings. He patiently answered, sometimes spending up to ten minutes on a dialogue between him and me. He always managed to include personal opinions in his answers, such as “I think this clearly shows the stupidity of Python1,” “What these modern programming languages are doing are invented by Scheme thirty years ago.”

His responses like this became frequent, and I couldn’t help but ask, “If these programming principles you advocate are so good, why haven’t they been widely adopted in the industry?” He would then pose solemnly, arguing, “Good design has no correlation with wide adoption!” and then he would start telling stories about “what the IBM vice president personally told him,” such as “the x86 system was adopted purely because it was terrible,” and so on, filling the classroom with a lively atmosphere.

My routine of asking questions became established, and one day after class, he proudly announced, “We have a questioner in our class!” From then on, every time he spoke, he would pause to glance at me, waiting for my query before continuing. Sometimes after class, he would say, “Thank you for asking so many questions—you allow me to philosophize, and slow me down just the right amount so that others can understand.” One time when I had to leave in the middle of a session, he would declare, “Our questioner has disappeared! Someone else has to ask all those questions!” Having received his personal approval, I became even more bold, relentlessly questioning his design principles and innovations before letting him continue. He indeed needed someone to ask questions—I had indeed heard from others that without my inquiries, the lectures were incomprehensible.

Part Three

All people will break, and when they do, they will be very broken. I am not broken yet.

Assignments in this course were also unusual. We would email our code to the old guy, and he personally graded it. When I received his response to my first assignment, I felt a mix of unease and gratitude. His reply went like this: “I’ve read your code from start to finish. In the comments of this function, you mentioned that you couldn’t think of a good identity function. Actually, your function could be written like this.” Then, he typed a revised version of the code in plain text in the email, detailing his testing process and results. “Also, these two functions of yours are very interesting; I’ve never seen them before. As for the extra question, even though it meets the requirements, I thought you might choose something more challenging.—GJS” Even TA in Intro to Programming don’t do thorough reviews like this.

At the start of the semester, as Scheme was a niche programming language, it was not easy to install. The old guy specifically set aside time, saying students who couldn’t install it could come to him for personal assistance. At the beginning of the term, when there were still many students in the class, about a dozen couldn’t get it installed, so he went from one student to another, installing it on each computer. He typed using only two slightly trembling index fingers; even using shortcuts was a challenge for his hand-eye coordination. Whenever he encountered a problem, he would murmur “Hmmm” and fall into thought. During these moments, I and the students nearby would exchange looks: indeed, programmers is a young man’s sport. Each time he identified a problem, he would get very excited, exclaiming “Ha! That is where it is!” and danced around, pointing out the issue to us. He continued this from 7 PM until 11 PM, until I, the last student, waved goodbye and left the classroom. That is when he finally relaxed, sat down, and took a sip from his water bottle.

During a private conversation, he proudly stated that he had seen every bug imaginable and could program much faster than us novices. I mentioned that he wasn’t typing as quickly as he used to. He waved his hand dismissively, “All people will break, and when they do, they will be very broken. I am not broken yet.”

Part Four

Once, they wanted me to be department head. When that guy walked into this office, I only said one thing to him: you have 5 minutes to leave the office before I call the police.

The old guy loved tea, especially Chinese tea. Whenever students visited his office, he would first pour a cup of Longjing for everyone before answering questions. One time, I tried to pour him some tea,

“In Chinese culture, it’s the youngest person at the table who pours tea for the others.”

“In Jewish culture, we don’t have bullshit like that. I’ll do it.”

He filled my cup and then his, grinning proudly, “I’m not religious. But do you know why devout Jews wear those little hats?”

“Why?”

“Because no one can make them take it off—in other words, no one is above us. Kings can send us to war, to die, but they can’t make us remove our hats.”

He always scoffed at power: “Once, they wanted me to be department head. When that guy walked into this office, I only said one thing to him: you have 5 minutes to leave the office before I call the police.” His love was reserved for his knowledge alone.

Once, I saw him lending a topology book to a student. When I asked about it, he inquired:

“Are you good at math?”

I answered honestly, “Not really. I’ve only studied linear algebra and probability.”

“Don’t you study anything else? That’s a pity.”

“What’s the use of learning it?” I was surprised by how hideous my question sounded. But I realized I was constantly doubting the usefulness of learning all these miscellaneous things every day. This old guy didn’t seem to harbor such self-doubt, so I sought his advice on how to achieve that.

“It’s useless for programming. But it helps your thinking.”

“What’s the point?” I threw another question at him, one I couldn’t answer myself. I always felt there should be some usefulness to thinking about so many things, but I couldn’t articulate what it was.

“It helps you see connections between different things.” He walked to the whiteboard and drew a triangle. “This is the Fundamental Theorem of Homomorphisms. It’s a mathematical theorem, but it also symbolizes the essence of science. This arrow is like building a model, that arrow is applying the model, and this arrow means that, in our consideration, we can disregard irrelevant factors. See, we can learn profound truths from mathematical theorems.”

I was moved by the beauty and simplicity of the theory for two seconds. “Then why not learn the truths directly?”

“You could. But pondering these connections is very enjoyable.”

“What else have you gained besides intellectual satisfaction?”

“What if,” he smiled mysteriously, “that is all I want?”

“What’s the difference between that and playing video games or doing drugs?” This was a question someone had asked me long ago, questioning why playing video games or chess doesn’t receive the same recognition as math. I couldn’t answer. I felt they were all manipulating symbols defined by human rules purely for intellectual satisfaction. The logic seemed odd, but honestly, playing video games seemed more useful, providing multi-sensory stimulation beneficial for various brain areas.

He was clearly not prepared for such a question, so he shifted to discussing the difference between pleasures bestowed by nature and those created artificially, which I found unconvincing. Neither of us had a good answer, but we pursue knowledge anyway.

Part Five

The system started as a ball of mud, but as you continue to rub that ball of mud, it becomes shinier and shinier and it takes on this regular shape; it becomes so intricate that people have to read a book and take a class to understand how to add to it. It becomes the jewel on the crown in the throne room of your mental palace, and you stop looking outside the walls - what is there to look at anyway? All you need to look at is in this room, right?

Unfortunately, I wasn’t very diligent in this course, sometimes quite willful. I still felt he was too conservative, failing to keep up with the evolving thoughts in the computing world, always muttering about technologies from decades ago. Despite being beautiful and intellectually satisfying, his lifetime effort in designing intelligent systems couldn’t compare to modern artificial intelligence built on computational power and data. Human intelligence is limited; computational power is limitless. There’s a famous joke in the AI field: for every linguist who leaves an NLP team, the accuracy improves by two points. The old guy, advocating human wisdom and symbolic logic, was like a mayfly shaking a tree in the face of connectionist neural networks centered on money, computational power, and user data. It’s possible that large language models could replace most programmers within a decade, including the old guy.

Out of distaste, I didn’t work hard outside of class. But this was an advanced programming course, and soon, I couldn’t keep up with the assignments based on my stream-of-consciousness understanding from the lectures. I asked him for an extension, and he said, “Sure, I don’t care about grades, nor correctness - what matters is that you put your thought into your problem set. You should show that you have learned something from me.”

I thought, isn’t that easy? I symbolically scribbled a bit, and that was it. So, I reread the chapter in his book related to the assignment back and forth three times, the more I read, the more I felt these programming patterns reflected his outdated thoughts. If I learned his methods, I’d end up like him, a decrepit old guy stuck in the programs he wrote years ago, abandoned by the tides of time.

After much thought, I changed my original plan and wrote overnight, submitting only commented code. The comments formed an essay titled “The Paradox of Elegance: Mud Huts and Diamond Palace.”

The code (link to GitHub Repo) began with a quote from the old guy’s book. “A diamond-like system is beautiful, but it’s hard to add anything to a diamond. If a system is made of mud, it might not look nice, but it’s easy to add more mud.” The TL;DR of the text was that the old guy’s ideas had become outdated in this fast-paced era. He didn’t advocate for complex, rigid systems like diamonds, preferring simple, flexible systems like mud huts, but he had long been trapped within the high walls of his own diamond palace, living comfortably but unwilling to venture beyond its walls.

;;; Author: Andi Liu

;;; Date: Mar 20

#|

Dear Professor Sussman,

I encountered some doubts while reading Section 3.2

(Extensible Generic Procedures) over and over again to

figure out the interfaces. The goal of submitting psets,

as you said, is to talk about what I have learned and what

I want to learn more about. This essay does just that. I

call it "The Paradox of Elegance: Mud Huts and Diamond Palaces",

and I am eager to hear your thoughts.

|#

#|

"Diamond-like systems are beautiful, but it is very hard to

add to a diamond. If a system is built as a ball of mud, it

is easy to add more mud."

In class, you discussed the distinction between diamond-like

systems and ball-of-mud-like systems. A ball of mud is simple,

flexible, and easy to modify, while a diamond is intricate,

rigid, and hard to modify. You advocate for the ball-of-mud

approach, using "generic procedures" that could be modified

after creation by adding different handlers that can be

applied to different situations. You argue that, after we build

procedures, they can often be adapted to new situations.

A monolithic chess program can only do chess, but a general

board game program initially written for chess can be adapted

to checkers. Arithmetic could be generalized by redefining

"plus" procedures to enable addition between numbers and

symbols, allowing a program that used to give you numbers to

give you a formula instead. You argue that this is what

generality means - this is the ball-of-mud system you can

always add to. You can develop a codebase over a lifetime,

know it inside-out, and the most significant pleasure is the

domain-specific insight it gives you, like understanding kinds

of rules a board game might have, or how this variable affects

the differential equation describing this physical scenario.

However, I think in a broader context, your system actually

resembles a diamond-like system, brilliant inside but hard to

adapt. Let me explain. Programmers program for a different

reason nowadays. Programmers today program to achieve goals, and

those goals are often constantly changing because what is

cutting-edge today is often obsolete tomorrow. Jupyter notebook

is a manifestation of this philosophy, where maintenance is

secondary to rapidly prototyping and testing ideas. Instead of

perfecting a code base, developers often abandon notebooks that

no longer serve their purpose. In this way, the focus is on

building up temporary "mud huts" that can be quickly discarded

in favor of new, more promising approaches. They shape their mud

huts however they like, and when the mud hardens, they just shrug

and find a new spot to start on a new hut that tests a different

architectural idea. In contrast, your philosophy of developing

a code base over a lifetime seems less adaptable, because while

you can easily switch from chess to checkers, they can easily

abandon chess and move on to Alpha Go, because their mud huts

are crappy so there is not much wasted effort. This idea of

minimum viable product and planned obsolescence is a uniquely

modern invention, where things are created not to last but to be

replaced, to be iterated on.

To contrast with mud huts, I would like to propose the metaphor

of a diamond palace with high walls to illustrate the limitations

of your approach. Once you have lived in a diamond palace for a

while (read SDF and figure out the codebase), you can very

comfortably do things you are familiar with. You know all the

secret shortcuts from this garden to that garden (how to change

a chess system to a checkers system), and, being the master

artisan that you are, can even extend the balcony of your palace

to see something further (extend your code base to do, say,

matrix calculation). However, the comfort of a familiar lifestyle

makes you forget there is a vast world beyond your palace and

its walls, a vast world where the mud hut people measure with

their feet. While it may have been easier for them to take the

time to building a palace and settle down, they stay nomads,

learning how to live in jungles, deserts, savannahs, etc. many

distinct things you can do with programming languages such as

machine learning, web development, system security) while you

grow more and more comfortable within your room (Scheme). When

you want food you don't go out and hunt deer (build entirely

new systems in new fields not possible to create by just extending

the system), but you have your chef make you a cake (extend the

existing system). Life inside a wall is easy, but if you get too

comfortable living inside the walls, they become limiting, and you

miss out on what is beyond the horizon from your balcony.

When you have a hammer, you see everything as nails; When you have

a code base, the only things you can think of doing are things you

can extend your code base to do. Programming language is not only

the vehicle of our thought but also the driver - in this case a

particularly conservative one that only drivers at 15 mph on roads

that it knows well. The system started as a ball of mud, but as you

continue to rub that ball of mud, it becomes shinier and shinier

and it takes on this regular shape; it becomes so intricate that

people have to read a book and take a class to understand how to

add to it. It becomes the jewel on the crown in the throne room of

your mental palace, and you stop looking outside the walls - what

is there to look at anyway? All you need to look at is in this

room, right?

|#

#|

---- Afterwords ----

I hope you don't see this essay as a personal attack on your

philosophy because it is not. I find your philosophies on

programming, general science, and life immensely interesting,

but I couldn't help but have doubt about its relevance in today's

fast-paced world. These are *inner* doubts: Everyone is moving so

fast nowadays, hopping from project to project, company to

company, and that can seem like the right way to do it, because

when you are starting you need to absorb wildly different ideas

like a sponge, right?

Only while trying to compose my ideas for this essay I realized

how well your philosophy worked out for you. You programmed for 40

years and developed a system that helped you solve anything you

are interested in. You could be content with taking a stroll in

the garden of your mental palace because you know this is all you

want. I can't do that. As a teenager, I have to go on adventures

and find out what I am interested in. So my task is not to extend,

but to establish.

Regardless, the metaphor of diamond and ball-of-mud is one I will

keep revisiting. The goal of contrasting two approaches is not to

start a holy war, but to reconcile, to find something in-between

that will work for me. On that note, please don't hesitate to

point out what I understood wrong to help me see better.

|#The reason I thought about all this was because I saw a part of myself in him—the part that studies purely for the interest in knowledge. This wasn’t a contradiction between him and me, but my own internal conflict. It seemed I was trying to prove that abandoning romantic illusions about academia in favor of pragmatism was the mature choice.

A few days later, I received his reply - in Scheme of course.

Part Six

Philosophy is meant to be attacked, because it is never “correct”. What is more important is that it is always OK to attack ideas, so long as we do not attack the people who have those ideas.

;; Hi Andi,

;; I just read your ps03 essay. It is very interesting. I

;; have carefully thought about it and I have learned something

;; from it. I am considering your points and want to argue

;; about some of them.

;; You are quite right that the purpose of this class is

;; inspiration rather than mastery of technique, so I am

;; certainly happy to give you ps03 credit for that work.

;; Your first paragraph is a pretty good summary of the ideas I

;; have been presenting in the class.

;; Your second paragraph (beginning with "However") seems key

;; to your argument.

;; It is indeed true that the infrastructure required to

;; support efficient generic procedures, for example, is quite

;; complicated, but once implemented it is no longer necessary

;; to look into it, in the same way you do not need to

;; understand how a compiler works to use the source language.

;; Sometimes it takes some serious effort to support a flexible

;; superstructure. The Jupyter notebook is exactly such a

;; rather complicated infrastructure built to allow rapid

;; prototyping. I am showing you other infrastructures, to

;; support flexibility, which are not covered by other

;; paradigms.

;; You argue that it is not necessarily a good idea to build a

;; complex infrastructure to support higher-level flexibility

;; because of there is not time, in the current business model,

;; to do that. You just have to produce novelty at a rapid

;; rate to survive in that environment. I think you are right,

;; if you actually think that the current business model of

;; development will continue into the future. But I suspect

;; that it will be gone shortly. I suspect that in not very

;; many years most "intellectual" jobs will be better done by

;; AI systems and there will be no jobs needed (including

;; professors) in that future world. So the only value of

;; creative work like programming will be for the pleasure of

;; the work and sharing that work with friends (as art and

;; music and literature are for the people who do it). My kind

;; of programming is partly aimed at that future.

;; Your third and fourth paragraphs are really where we

;; disagree. I am quite aware of that other world, outside of

;; my constructed palace. I am trying to show you how to build

;; a palace of your own, independent of the base system and

;; language. I know that is not the prevailing wisdom of the

;; computer-science "professionals". But I do not believe in

;; the long-term viability of their approach, partly for the

;; reason described above, but also because I see the very bad

;; quality of the software that results from that approach.

;; How much novelty do we want? There are tradeoffs between

;; novelty and longevity, quality, and reliability of systems

;; based on software.

;; But I want to emphasize that the SDF book is NOT about how

;; how to adopt MY codebase and how to use it. It is to

;; illustrate the advantages of making such a "palace" and

;; showing you that it is not very hard to make one for

;; youself, on whatever platform you have, as needed.

;; Anyway, I never worry about "a personal attack on my

;; philosophy". There are two reasons: Philosophy is meant to

;; be attacked, because it is never "correct". What is more

;; important is that it is always OK to attack ideas, so long

;; as we do not attack the people who have those ideas. I

;; learned very early that it is both fun and illuminating to

;; argue about ideas. So have fun :-)

;; GJS

;; BTW: I started programming in 1962, on an IBM 650 in machine

;; language, so I have been programming for over 60 years

;; (mostly recreationally)! My friend Chris Hanson has been

;; programming professionally for over 40 years (27 years for

;; me at MIT and 16 years in industry, 10 of those years at

;; Google), so together we have over 100 years of programming

;; experience.The old guy prides himself on being a scientist, engineer, and a fighter in the free software movement. He’s an engineer, so he must build what he talks about. He’s a scientist, so he must be able to explain what he builds. As a free software advocate, he believes all code should withstand scrutiny. His reply aligns with his own standards.

But he is indeed stubborn. To win our argument, he’d deny the practical value of his job.

Part Seven

He said that when he was a teenager, he decided to devote his life to intellectual satisfaction. He doesn’t do anything that isn’t fun. I asked him, do you really just read books and think about problems every day? I enjoy reading too, but my brain gets tired after a while. Can humans really enjoy such sustained intellectual engagement?

He said yes. “Anyone who graduates from MIT can make a living. The important question is, what is beyond that?”

I felt ashamed. I always felt like I was choosing between the moon and sixpence, believing I attended programming classes and sought internships out of necessity, not choice. In my mind, the old guy chuckled and said, you could put down the butcher’s knife and become a Buddha right away; why don’t you put it down? He was right. This wasn’t a choice between the moon and sixpence; it was a choice between a million pound note vensus the moon and sixpence. Perhaps I am more practical than I thought. I don’t have his willpower.

Or maybe it’s because I’m not an old white man. As an international student, I carry a heavier burden than he does.

Part Eight

You might think he’s an old sage who just drinks tea, reads books, writes code, and ignores worldly affairs. But that’s not entirely true. He also enjoys talking about his wife.

Once, I visited his office. He mentioned that his wife Julie might be around. I knew Julie Sussman was a book editor and her name appears on the cover of his famous book, thanked for maintaining “the Gerald Sussman Project” for decades. The old guy reminisced about their passionate years: they were both in MIT’s math department, she was a year behind him. He lived in Baker; she was in McCormick…

As I browsed through his office books, we chatted. I pointed out a formatting error in one of the books, and he seized the opportunity to boast, “That’s because he doesn’t have a wife as good as mine.”

Once, he asked me to explain the Chinese characters on a tea package. After I explained why “ecological tea(生態茗茶)” had nothing to do with “lively bear,” he mischievously handed me a small book titled I can READ that! A Traveler’s Introduction to Chinese Characters by Julie Mazel Sussman. I flipped to the author’s bio, which listed nearly ten languages she spoke.

“Haha, she speaks many more languages now! She’s very interested in Bulgarian lately.”

I skimmed the book. She is right. I can read that.

Once, while we were chatting, a lady with bunny ears appeared at the door.

The old guy naturally asked, “Why are you wearing bunny ears? They look very fluffy.”

Then she noticed me, and I awkwardly waved. She might have been shy and walked away. I’m still not sure if she was Julie.

Part Nine

He is logically consistent with himself, but he rarely acknowledges others’ logic. That’s why he invented his own language and wrote his own interpreter. HIS language ran using HIS interpreter on HIS machine acknowledges him.

Even though we got along well personally, my dissatisfaction with his teaching grew. Once in class, he excitedly talked about a program he developed last summer. “Do not expect this to be easy. I don’t even understand what is happening.” It was not easy. I didn’t understand a thing from that lecture. My notes were full of complaints.

“He talks about too many things.”

“He probably thinks everyone should spend 9-12 hours a week reading his code, but I really don’t think my time should be spent on things that have been left behind by time.”

“He’s both an engineer and a scientist, but he’s not a good teacher. The conversations I have with him as an engineer are more fruitful than those I have with him as a student and teacher.”

“He is logically consistent with himself, but he rarely acknowledges others’ logic. That’s why he invented his own language and wrote his own interpreter. HIS language ran using HIS interpreter on HIS machine acknowledges him. 2 ”

Part Ten

People coming out of MIT find it easy to impress others. Impressing yourself is the hardest part.

As always, the old guy poured me some Dragon Well tea. My hand trembled slightly as I picked up the cup. I knew that this visit to his office was not just for tea.

We chatted for half an hour about science, philosophy, artificial intelligence, and the future of humanity. He showed me his latest article discussing general artificial intelligence, still the old tune of symbolism, believing AGI should be composed of various modules, with the challenge being to link them.

The distant future and the pressing present melded in my mind. The next class is attendance mandatory, and if I don’t speak now, I’ll miss it.

“Sorry to interrupt. I came to your office today because the drop date is around the corner.”

“Right. You have to make a decision. I can’t make that decision for you.”

“About the assignments…”

“Your assignments, if you catch up, I’ll give you a passing grade. But I only guarantee passing—it won’t be pretty—you’re really quite late.”

Hearing this, I made up my mind. I took a deep breath.

“I understand. I’ll change this course to listener.”

He seemed to be waiting for a reason.

“I find this course fascinating, and I’ve learned a lot from you. You are a role model as an engineer and scientist. But I don’t need this course to graduate, so there’s no need to let it affect my GPA.”

When I said the letters GPA, my heart sank. He was not wrong to give me a passing grade; I really hadn’t worked hard enough in this advanced programming course. I felt ashamed to demand such a utilitarian measure from a man who cared nothing for worldly standards.

“What’s the use of a GPA?”

He wanted me to personally tear apart this veil of romanticism.

“A GPA is useful for getting a job or applying to grad school. Higher is always better than lower—”

“Do you really want to go to grad school?” he interrupted. “Many people want to go to grad school, but they don’t understand what that means. Once you’re in grad school, your work is judged by yourself, not by others.”

“Isn’t it bad if your happiness depends on others?”

“It’s not. People coming out of MIT find it easy to impress others. Impressing yourself is the hardest part.”

“But didn’t you go to grad school?”

“Yes. My personality suits grad school. It’s not for everyone.”

I hadn’t decided whether to go to grad school. But he was right, his personality really suits deciding his own happiness.

I enjoy seeing the connections between things, but I can’t allow myself to live solely for my intellectual satisfaction. I’ve received the best education, possess above-average intelligence, and enjoy many privileges. Satisfaction for me is too easy to achieve: reading fiction, videos games, and academic research in the ivory tower are all painfully comfortable. But I feel that path is indulging in an illusion, avoiding the various challenges of reality.

I want to do things that impact others. I can’t afford to be content like him, thinking the industry is foolish and the good old days are past if my ideas aren’t adopted. If I truly believe in an idea and it’s not adopted, I’d think the problem is in how it’s communicated. I’d find a compromise to make the idea less pure but more widely accepted because the idea isn’t just for me—it’s for everyone.

No matter how much I enjoy sitting here drinking tea and discussing math, science, philosophy, and logic with the old guy, I need to return to the real world. After the next class, my Toy Product Design teammates are waiting for my code and circuits, my System Design teammates are waiting for me to finish my part of the protocol, my side project is just starting… These may all seem like trivial matters to the old guy, but without handling these small things, nothing significant can be achieved.

When I left the office, he said:

“No matter whether you continue to take this class, you are always welcome to come to this office and have tea.”

Part Eleven

His Scheme, the programming language he invented—the simplest, freest of languages—wasn’t this language, in essence, just himself?

I didn’t attend the old guy’s classes for the next two or three weeks, but I went to his last lecture of the semester. The class was titled “Why Programming”.

I pushed the door open. He nodded at me. I breathed a sigh of relief. I sat down. He began:

“This is a very personal class. The concepts I teach in this class are completely opposite to those taught in other programming courses at this school. They emphasize correctness, following specifications. Traditional software engineering doesn’t want talented programmers, but replaceable ones.

This class is a counterbalance. I emphasize not correctness, but rapid-prototyping; not planning how to follow requirements before writing, but understanding what you want in the process of writing. This class is a breadboard, not an ic-board.”

I had soldered circuits for ten hours the day before yesterday, and I deeply appreciated his analogy. Soldered circuits are difficult to modify, while unsoldered circuits, though often malfunctioning, are easy to adjust, bringing many possibilities.

The basic architecture of general programming languages is hard to change, but with Scheme, the old guy could overload addition with a few lines of code, making all 1+1 not equal 2 but 1+1, trading the ability to perform addition for the possibility of symbolic algebra. High freedom brings high risk, and only those who deeply understand what they’re doing can harness such freedom.

“This is why I never limit myself to one tool. Tools are meant to serve people. I’ve always disliked object-oriented programming (OOP)—it’s popular, but it can’t solve everything; and if you only know how to use a hammer, everything looks like a nail; if you think everything can be solved with OOP, you’ll bend the problem to fit into OOP: here, the tool actually limits the thought. But Scheme is not purely functional programming either—I don’t like the word pure.

An engineer cannot afford to be too fixated on any particular tool or ideology. Most of the time, I like my programming to be functional, but if something is simpler to do in a non-functional way, I know I always have that option. Sometimes a hammer is just what you need.”

Indeed, the old guy was clear when it was time to break his own “laws.” That’s what I like most about engineers: their words must be based on real constraints. Engineers can have all these philosophical debates, but ultimately they are also the one actually building stuff; so they understand it is just a matter of what tool is more appropriate in different situations.

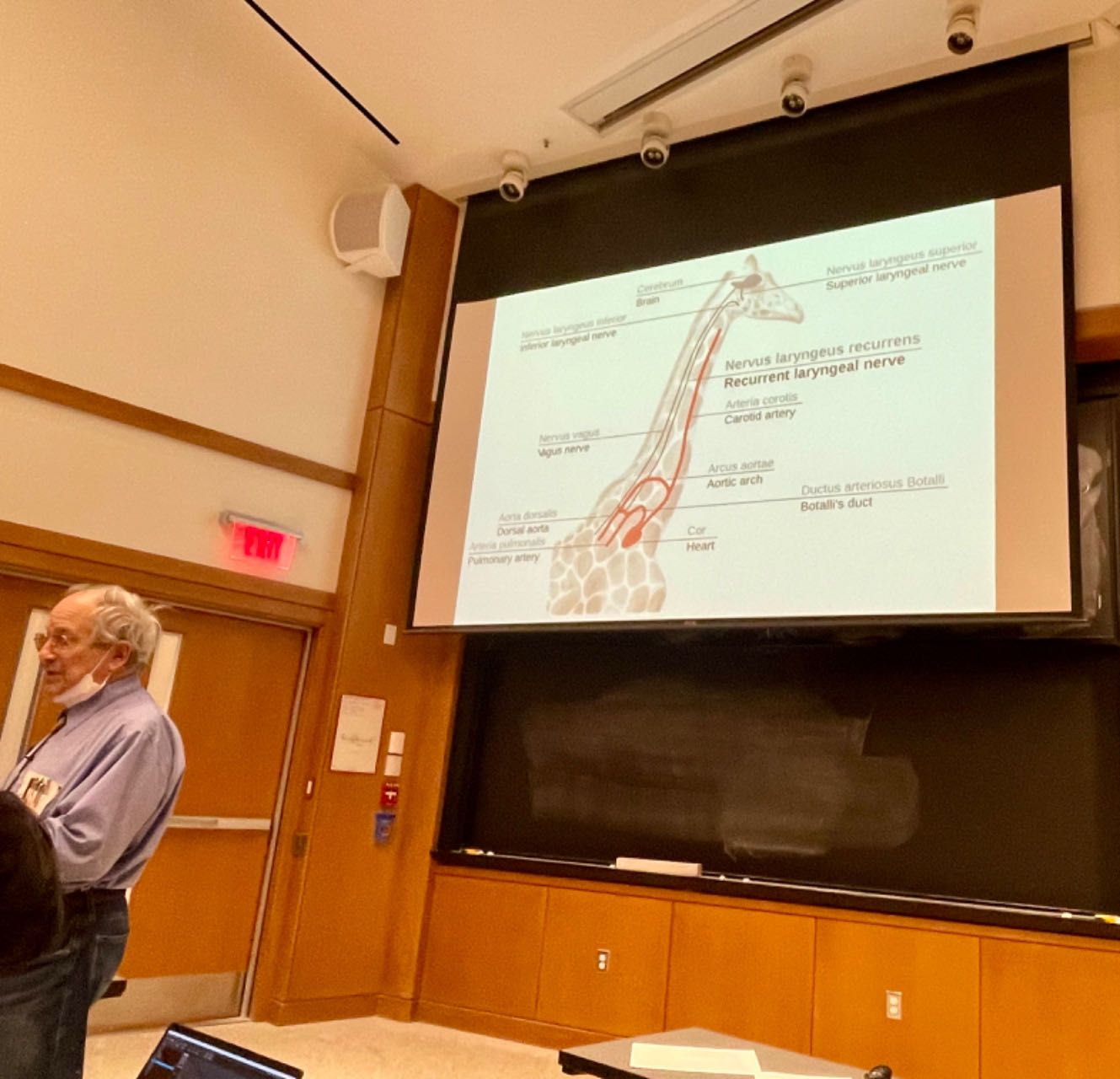

The old guy then listed the teachers and friends who had greatly influenced him, with a series of black-and-white photos in front of him. Marvin Minsky, Seymour Papert, John McCarthy, Richard Stallman, Richard Feynman (Feynman invited him, and they taught physics together for a year, under the condition that Feynman would have lunch with him after lectures)…

I heard how each person’s theories and work influenced him. It was a fascinating feeling, seeing the most rigorous and mechanical theories backed by vivid individuals and their lives. The old guy’s theories filled my senses: his composition and use of color were influenced by which era, which movements; his musical style and choice of instruments stemmed from which culture, which region; his writing style, his choice of words, his language… his language! His Scheme, the programming language he invented—the simplest, freest of languages—wasn’t this language, in essence, just himself?

The old guy’s Scheme is the Latin of programming languages. It’s a language that only the smartest among a smart group, programmers, can handle. It’s the language of the elite, elegant and mentally stimulating, but in this era, it has no practical production value, no large audience. But I can’t say it’s merely the language of peasants. This is also the conflict between symbolism and connectionism—symbolism cares only about human intelligence, while connectionism cares only about experiments and stacking computational power…

His last class ended.

“Question!”

“Yes, sir!”

“So, why programming?” Although it was somewhat obvious, I wanted to hear his personal answer.

“Well, because programming is fun.” He said matter-of-factly. “Also, it allows you to express what natural language can’t. You know, if you figure out what you want, you can also roll your own language.

But the hardest part is figuring out what you want.”

I still don’t know what my path of “doing real things” will look like, or how to walk it. I only know that I need to meet enough people and stay open-minded to the most contradictory ideas to form my own language.

Part Twelve

Opinions about him vary.

Some say he’s a nice old guy who likes to chat with students over tea.

Some say he loves to digress, always managing to publicize his own class when giving recitations for other classes.

Some say he always talks but never listens. But if there is one good thing about him, it is that he is a living example of how you can do whatever you want in life. He wanted to spend his life programming in Scheme. He did just that. He seems happy.

What if… personal happiness is not all I want?