After I Proved P = NP

Some would say it was GPT-5. Some would say it was Sipser's cat. Some would even claim he’d channeled Alan Turing’s spirit.

2023-8-18

P = NP

One day in my sophomore year, I thought I’d discovered the solution to the famous unsolved computer science problem, P = NP. In 24 hours, I went from doubting myself to doubting reality, then into pure euphoria, before finally settling back into disillusionment.

It all started with an assignment from our 18.404 class. The question mentioned an algorithm that could solve the 2-SAT problem. Naturally, I thought, “Why stop there? Why can’t this work for 3-SAT? Why can’t this prove P = NP?”

(For context: 2-SAT is a solved problem, but 3-SAT has no known polynomial solution. If a 3-SAT solution were found, it would prove P = NP.)

So, I did some quick mental math and ran it by a classmate, and since we couldn’t find any obvious flaws, I decided to sleep on it and tackle it fresh in the morning.

After all, if I were right, the foundations of theoretical computer science would crumble, and history itself would be changed. Countless computer scientists, including Sipser himself, have dedicated days and years to this problem. Could Sipser really have casually slipped a solution to P = NP into our homework?

The next morning, I still couldn’t find any holes in my theory. In the EECS lounge, I spotted a grad student I knew heading out for breakfast and thought I’d ask her to check my proof.

“Hey! You’re in 18.404, right?”

She replied, “Yes I am! Hi Andi, how are you doing?”

“Doesn’t matter. Have you looked at the homework problems yet? Because I think I’ve just proved P = NP.”

Short, awkward silence

Her: “Umm, I’m pretty sure you didn’t? Sipser’s spent a lot of time thinking about it. There’s no way he could…”

Then, I heard Sipser’s voice echo in my head from one of our lectures:

I myself have spent many years thinking about whether P is equal to NP, perhaps too many. So, why is it so hard to prove we can’t compute NP efficiently? Because we’re up against a formidable foe here – human intellect.

So, I said, “Maybe he’s too OLD for this.”

Her face shifted from “I’m excited for breakfast” to “I’ll have to starve for a while.”

“Oh, you’re one of those people.”

“Yep. Here’s how the algorithm works…”

She didn’t point out any flaws (or maybe she just really wanted breakfast). Throughout the day, I had similar conversations with sophomores, juniors, seniors—they all started out as skeptics, but by the end of each conversation, no one could poke a hole in my arguments. With each retelling, my initial “there’s no way I’m right” attitude turned into genuine confidence.

I even joked to a senior, “I am going to finish grad school before you do.”

In my head, I’d already imagined myself on the front pages, lecturing passionately at conferences, while engineers worldwide scrambled to fix their broken encryption systems. Nineteen years of total obscurity, and now here I was, Yitang Zhang 2.0.

Finally, I put my theory to the ultimate test: I asked Professor Sipser himself on Piazza, “Why doesn’t this algorithm prove P = NP?”

After a few back-and-forth clarifications, he said, “Uh, that’s not quite how the algorithm works…”

“Oh.” Then it hit me: I had misread the problem entirely. My so-called “algorithm” was totally invalid.

And I remembered Sipser’s words from another lecture:

People have been sending me letters for decades, claiming to have proved P = NP or P ≠ NP. Eventually, I just stopped responding. Not really worth my time.

Turns out, if I had understood the original problem statement correctly, I wouldn’t have even known how to solve the assignment problem. My meteoric rise to “computer science prodigy” and crash down to “student who can’t solve his own homework” happened in the span of a day.

But then I thought of Yitang Zhang, who spent years publishing under a flawed advisor’s conclusions only to have it all overturned—a journey that took him over a decade. I, on the other hand, misread a single problem and took only a day to fall from grace. Not too bad, really.

Programmers around the globe can relax for another day.

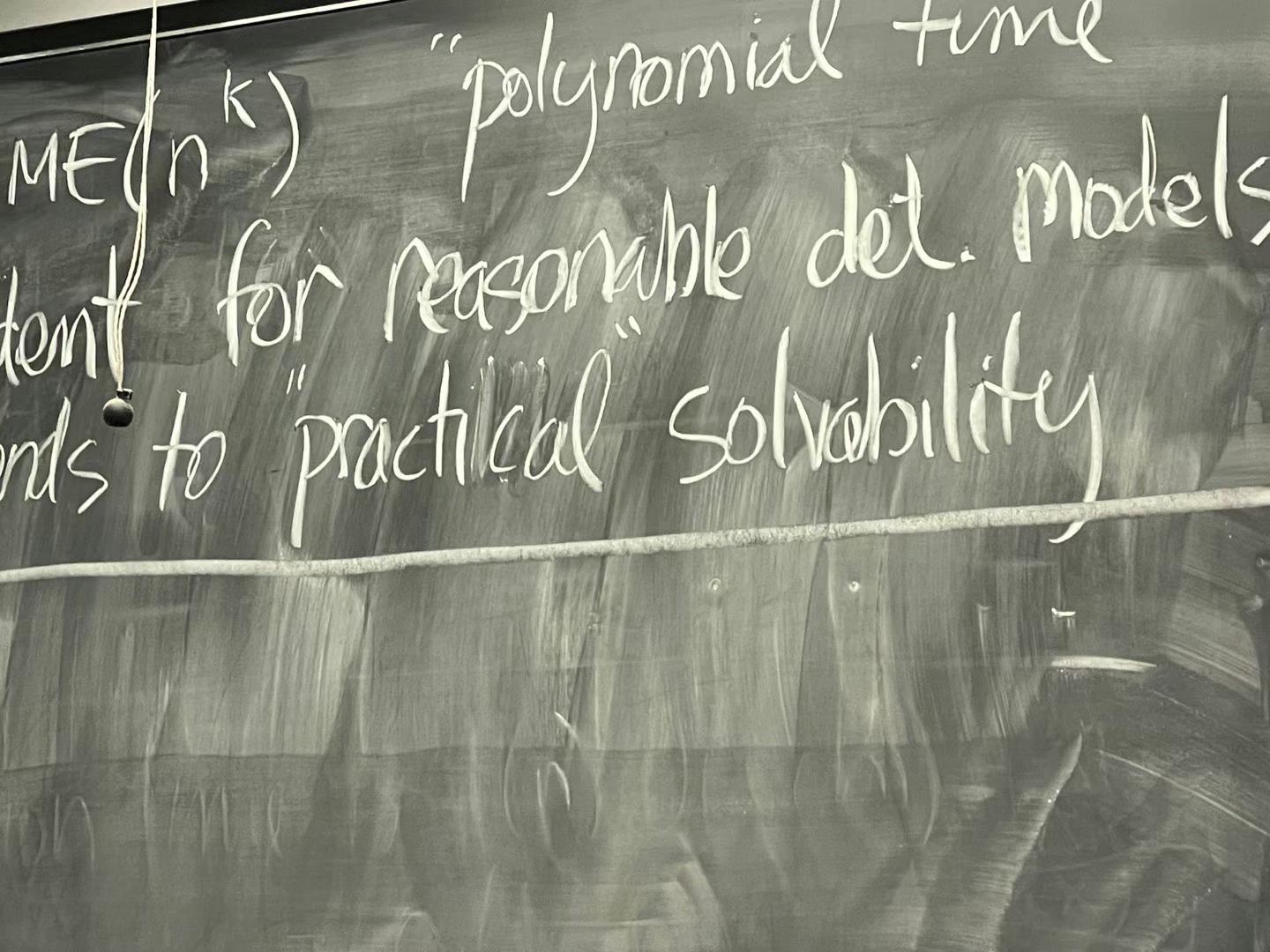

He paused at the word “practicle,” gave a thoughtful scratch of the head, and then, with a wry smile, corrected the typo. It was a rare nod to practicality in a room otherwise steeped in pure theory.

P ≠ NP

Fast forward to finals week. In a practice exam for 18.404, there was a true/false question with the options “Yes,” “No,” and “Open Problem.”

It looked false, so I confidently chose “No.” But the answer key said “Open Problem,” because the question boiled down to the P = NP problem. I didn’t want to mark myself wrong.

How cool would it be if this question were to appear on the real exam, and I could prove P ≠ NP right then and there?

Then an idea suddenly hit me: I could prove P ≠ NP using Shannon’s information theory. A rough sketch of the proof quickly appeared in my mind.

And then, daydreaming took over.

You see, unlike the many failed attempts with diagonalization, my proof would go straight to the core of nondeterministic vs. deterministic computation. It would bridge seemingly unrelated fields. How poetic would that be!

More importantly, if I were right, my answer to the multiple-choice would be the only correct one. The rest of the class, who marked it as an open problem, would all be wrong due to this unexpected breakthrough, and I’d earn a solid four-point lead.

If the TA marked my answer wrong, I’d show him my proof. He’d definitely be skeptical—until, after a solid two hours of writing on the whiteboard, he’d start nodding along and eventually propose that we write up an urgent email to the professor.

Sipser, no stranger to “breakthrough” letters, would tell us to wait until the next day. And so, the next morning, he’d stroll into his office with a cup of tea only to find two exhausted students slumped at his door, surrounded by stacks of paper.

He’d wake us, listen gravely to our explanation, until he forgot to add water to his teacup and started chewing on the tea leaves. Half an hour later, he’d stand up, draw the curtains, and whatever happened in that room… no one would know. But the news would soon spread: Sipser had finally published the paper of his life, titled “P ≠ NP.”

What everyone would talk about most, though, is that Sipser was only the second author. The first author was listed as “Anonymous.”

Speculation would run wild as to who this mysterious “Anonymous” first author might be. Some would say it was GPT-5. Some would say it was Sipser’s cat. Some would even claim he’d channeled Alan Turing’s spirit.

But Sipser, ever elusive, would reveal nothing. And when the Turing Award committee came knocking, he’d simply wave them off, saying the first author preferred anonymity.

As for me? I’d keep my identity under wraps because I knew I wasn’t a genius. I didn’t want to handle that level of expectation. I was just a regular programmer who wanted a quiet life.

Every few years, the three of us would occasionally get together and grab a cup of tea.

Many years later, Sipser would take our secret to the grave.

I’d attend his funeral, locking eyes with my old TA, now a big name in theoretical computer science, with the same unkempt hair he had when he taught my recitation. After the service, we’d sit outside Sipser’s empty office in silence. Eventually, I’d doze off, only to wake and find the TA gone, in his place a bouquet of white lilies. We’d never see each other again.

I’d retire as an ordinary software engineering manager. On my deathbed, I’d confess this secret to my partner and two kids. They’d find my original proof on the back of the practice exam sheets, and the world would be shocked. But I’d already be gone, at peace.

Back in reality, this whole story was just a daydream. I wandered inside my dorm excitedly, until I ran into a senior who I could check my proof with. After an hour of heated debate, I finally realized my “proof” couldn’t even provide a lower bound on the complexity of a basic sorting algorithm, let alone tackle P ≠ NP.

She let me know she had a final project to finish, and I slunk back to my room, knowing that my answer would have to be marked wrong.

Looking back, I spent two hours dreaming about my future fame, but it only took one hour for reality to bring me back down.