My Startup Lessons with TimeTrace

I think of engineering and product like the roots and leaves of a plant. A project needs the stable foundation of engineering and the “photosynthesis” of product to grow strong.

2024-9-23

During my junior year, I worked on a startup project with a few friends. The project is called TimeTrace, and our team includes five MIT students and one Princeton student.

At first, I envisioned TimeTrace as an app that would record all your screen activity. We ended up building a Chrome extension, which now has a small user base on the Chrome Web Store and has been launched on Product Hunt as well.

Looking back, we made quite a few mistakes on this first venture, but I’ve also gathered some key takeaways, which I’d like to share here in the form of stories.

Lesson 1: Start with a Proof Of Concept (POC)

Imagine I tell a car factory I want to build a car. The engineer there says, “Alright, but you need to hand us the blueprints, exact measurements, and materials.” But all I have is a piece of paper with a crayon drawing of a little red car.

That little crayon car drawing is my Proof of Concept. It might not look impressive, but sometimes these rough sketches do wonders in moving an idea forward.

Think it sounds absurd? Well, when I was first starting this project, my “crayon car” sketch is what convinced my future tech lead Chengyuan to join the team.

So, let’s rewind to the beginning of my junior year. Back then, I had no team, no project, just a bunch of wild dreams and an itch to build something.

I’d signed up for fourteen classes, but within a month, I dropped eleven, leaving just three.

I didn’t know what I wanted to do.

I’d already tackled the core computer science courses. The remaining advanced courses felt too niche and might not even be useful for what I wanted to do—if I ever figured out what that was. So, I dropped class after class until any further drops would officially make me a part-time student.

I consoled myself with the idea that sitting in class wasn’t exactly effective learning anyway. With this free time, I could finally focus on “active learning”—at least that’s what I told myself.

While zoning out in lectures, I’d jotted down plenty of ideas. Now, with all this free time, I started pitching them to my friends.

One of these pitches was to Chengyuan Ma. He is a very cracked programmer. The Chinese international students call him “Teacher Ma” out of respect. While we’re both MIT CS students, we’re about as different as Turing and a machine—like, even though we go together, but one knows how to code, and the other doesn’t.

So one night, we’re in my dorm room. I start pitching him my brilliant idea for a screen activity tracker. I tell him how it could revolutionize human-computer interaction, putting Notion and OneNote out of business. He listens as I go on, describing every detail in full-blown startup pitch mode. When I finally stop, he says:

“I think this would be pretty hard to build. Even something simple, like tracking the active app on your screen, would take at least a hundred lines of code.”

I scoffed, “Come on, it can’t be that hard.”

He shrugged and said, “Talk is cheap. Show me the code.”

This is one of the biggest differences between technical people and business people when it comes to entrepreneurship. If I wanted to convince a developer to join me, I needed code, otherwise I am just like a business student with no business skills. Code is the developer’s handshake.

So, there it was. I just need to code it out. Easy, right?

But here was the problem: Chengyuan is a better coder. If he needed a hundred lines for the prototype and a few hours, I’d probably need two hundred, and it could take me all day.

But even though I couldn’t magically pull a prototype out of thin air, I could still whip up something simpler—a Proof of Concept.

I mean, if I couldn’t create a detailed blueprint, I could still give him my crayon car. If every idea required fully fleshed-out blueprints just to get started, then a lot of projects would never take off. Honestly, a lot of great ideas start out as a little crayon car drawing.

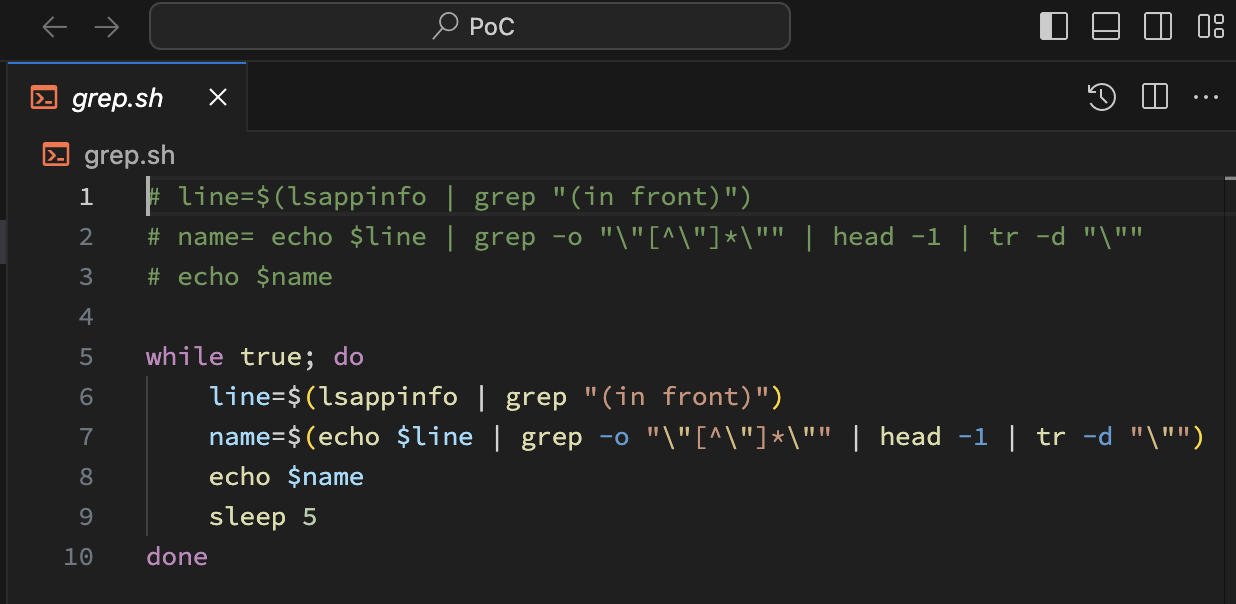

I remember Googling how to code this, but all the examples I found were way too complex. I wasn’t about to dive into that, so I kept searching. Finally, I found a simple solution. Then, with a little help from Stack Overflow and ChatGPT, I managed to write a basic program that printed the name of the active window every five seconds.

“Look, here it is! Just six lines of code.”

Chengyuan tested my code. Sure, it was crude, but it proved the idea could work. After a brief silence, he said:

“I think I can finish the prototype tonight.”

And that’s how TimeTrace got its start. That initial POC code never made it into our final codebase, but the idea behind it influenced our entire technical design. A good POC not only convinces people to join you but also shapes the direction of the product.

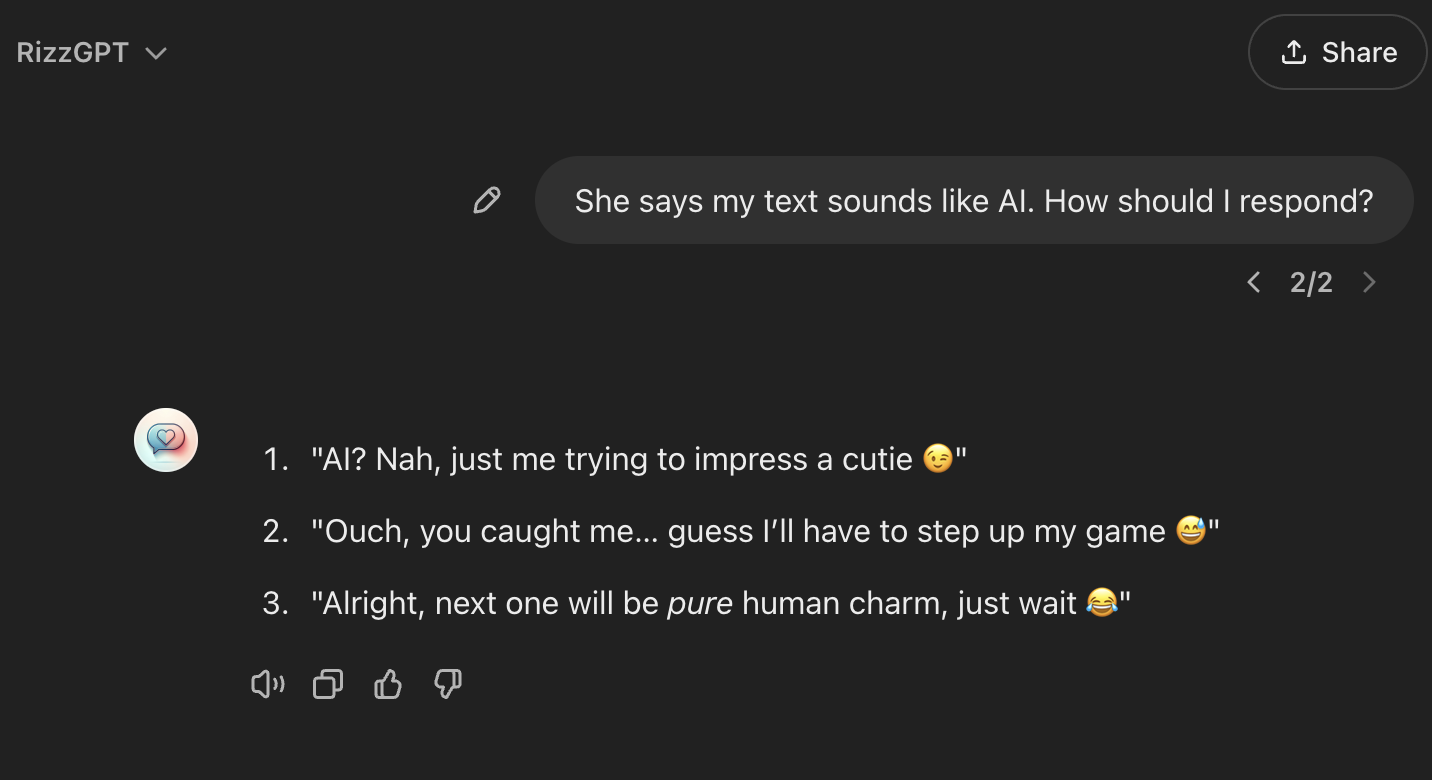

By the way, besides TimeTrace, I was pitching other ideas back then too—like RizzGPT, your personal texting coach. But after testing, I realized ChatGPT was quite awkward at flirting. I dropped it. A failed POC can save you tons of time—better to fail fast than to gather a whole team and only then realize it’s a dead end.

Lesson 2: Smart People Are Not The Same

In class projects, everyone tries to latch onto the “cracked” person in the group. And in startup recruiting, it’s all about hunting for the smartest people.

But pretty quickly, I learned that smart people are not smart in the same way; there are all kinds of “genius,” and not every “big shot” is a great teammate.

Take this experience. After my pitch, Chengyuan mentioned he had a friend who was interested. I was pumped—imagining this friend must be another coding master. I had Chengyuan create a group chat, and we set up a Zoom call.

Sure enough, the friend knew his stuff. I showed him my six-line POC code, and the three of us were off to the races, brainstorming possibilities for the future.

Then we got to the part where we needed to divvy up tasks. He mentioned he had finals coming up and might not be available for the next two weeks.

No problem, right? Fast-forward past finals, and he tells us he’d pushed himself too hard last semester and now needed a break. Months later, I reached out again, and he asked if we were planning to “make TimeTrace an actual product instead of a toy.” I said yes, and he told me that didn’t line up with his interests—he preferred research over software engineering. That’s when we had the “formal exit discussion.”

Lesson learned: not every super-talented person should be a teammate.

Now, you can broadly categorize talented tech folks by what motivates them. There are two main types: engineers and researchers.

On the outside, both engineers and researchers write code and are wicked smart, but their goals are worlds apart. Engineers get their kicks out of polishing a product and tweaking details; they’re all about making it work perfectly and look beautiful. Researchers, on the other hand, chase the intellectual thrill of solving interesting problems—they’re in it for the brain candy, not the fine-tuning. They’re fun to brainstorm with and great for bouncing ideas off, but if you need someone to cater to user needs, polish a product, or show up for weekly meetings, they’re probably not the ones for the job.

In class group projects, it’s tough to see this distinction because engineers and researchers are usually both just trying to get an A. But in a real project, the difference is crystal clear. Especially early on, when there’s no visible outcome, what keeps a project alive is internal drive. Engineers and researchers have totally different drives, so if you want them on your team, you’ve got to manage your expectations and find different ways to motivate them.

And of course, engineers vs. researchers is just one way to categorize people—there are so many dimensions. Take our two PMs on TimeTrace, for example. One has a knack for steering the big-picture direction during meetings, with a natural sense for where things should go. The other prefers doing extensive pre-meeting research and letting data guide decisions. In casual settings, you might not notice the difference. But in a work environment, if you don’t take time to understand different work styles, things can get pretty chaotic.

Through this whole experience, I’ve come to appreciate just how wildly different “smart people” can be. For me, the joy of working with a team is noticing these differences, using everyone’s strengths, and making sure people are doing what they enjoy. When you’re putting together a team, those differences in work style are something you can’t afford to overlook.

Lesson 3: Engineering and Product Need Balance

Earlier, I talked about how people in the same role can have wildly different working styles. But the differences across roles? Those are a whole new level. In our team, we have devs and product folks, each with their own distinctive quirks.

Devs hate meetings. If they’re forced to join one, they keep their cameras off, only speak when directly called on, and want it over ASAP so they can get back to coding and getting things done. Their favorite action item is “refactor the codebase,” which is like cleaning up a messy room. It means rewriting existing code in a more “elegant” way that doesn’t change any features but somehow makes them feel refreshed, ready to churn out new code.

Product people, on the other hand, need meetings. They have to tell the devs what to build and how, to make sure the code turns into something valuable for users. They love brainstorming thoughtful, unique features to release ASAP. The issue? These thoughtful, unique features aren’t always simple to implement, and rushed deadlines can lead to “technical debt,” which is basically a pile of unfinished work that eventually requires a “code cleanup day” to pay it off.

These two groups have goals that don’t always align—and sometimes even collide. So, how do we work together?

This is where a mediator is needed, and that mediator is me. I live in both worlds, with one foot in dev and the other in product.

To the devs, I’m the voice of product. To the product team, I’m the voice of dev.

Take the time we were deciding on TimeTrace’s tech stack. Chengyuan proposed a particularly complex design.

I argued that a simpler design would work just as well and save us time.

But he reminded me of our last project (DormSoup) together, where we rushed the build, and the code turned into a “mountain of spaghetti.” He wasn’t eager to repeat that.

I replied, “If we hadn’t pushed to launch right before freshman orientation, we’d never have gotten a thousand users. You can make your solo project code as pristine as you want, but how many people will see it? Twenty-one GitHub stars. We’re building for users, which means features, speed, and iteration.”

Twenty-one stars—Chengyuan’s crowning achievement. Since his projects mainly solve his own problems, his potential users are basically hardcore programmers, which, surprise, is not a huge crowd.

He didn’t have much of a comeback, muttering, “I’m an engineer. Pessimism is my job.”

Back in my room, I felt a bit discouraged, thinking he was too focused on engineering to see the product perspective. Then I reconsidered—our collaboration is valuable because we see things differently. Otherwise, we’d just be talking to a mirror. My real value comes from seeing both the engineering and product angles.

In the end, we went with the simpler design, saving us a ton of time.

Then there are the times I have to represent dev in front of product. In product meetings, I’m the one evaluating the feasibility of proposed ideas.

They’re often baffled by my time estimates. For instance, redesigning an entire page might take five hours, but aligning two lines afterward could take two more. Adding an AI chatbot might only take six hours, but emailing a user a graph that could be done in Excel? That’s ten hours. Making a line thicker might be five minutes, but swapping a checkmark icon for an eye icon? Practically impossible.

Sometimes, they just don’t get why a seemingly simple feature can’t be added. If you haven’t done development, it’s hard to anticipate the hidden costs—maintenance, different screen sizes, UI library limitations, and so on.

And I’m not always right, either. Once, we piled on so many new features that the older ones broke, and no one noticed. Chengyuan protested, saying we should extend the deadline, focus on existing functionality, and do proper PR reviews so devs could check each other’s code. I was dead against it, thinking it would slow us down.

But once we extended the deadline and did PR, bugs dropped, and refining existing features improved user experience. It was clear our high-pressure, low-quality approach wasn’t sustainable. This time, the devs had it right.

In The Hard Thing About Hard Things, it says a CEO’s job is to speak for the person not in the room. Though I’m not a CEO, I feel this deeply.

It’s a lonely job. Once, my PM said my engineering mindset was too strong, “more dev than product.” The devs, though, see it differently. While coding with them one day, a dev joked, “Is Andi back on the dev side?”

But a good project needs both sides (and more, like a UI/UX designer). Product wants to roll out as many features as possible to satisfy users, while engineering makes sure those features are realistic and implementable.

If it’s only product, nothing gets built; if it’s only engineering, whatever gets built won’t have any users. Projects live in the constant back-and-forth negotiation between product and engineering—both are essential.

I think of engineering and product like the roots and leaves of a plant. If product overwhelms engineering, it’s like a plant with shallow roots that can be uprooted by the wind. If engineering overwhelms product, it’s like a deeply rooted plant that never blooms or bears fruit, bringing no value to the world.

A project needs the stable foundation of engineering and the “photosynthesis” of product to grow strong.

As our team has developed, the relationship between engineering and product has evolved too.

Early on, with neither side experienced in working with the other, there was plenty of friction and inefficiency. Our weekly meetings ran two hours with hardly any action items because the ideas product pitched were often far from what engineering could realistically achieve. And sometimes, when product asked for time estimates to set priorities, engineering refused, “not wanting to overcommit.”

But through discussion, engineering began to see why product needed time estimates, and product started considering engineering’s feedback more. Team meetings shifted from starting with product to starting with engineering, so product could hear engineering’s thoughts first. We went from a “make-do” collaboration to mutual understanding and information sharing.

There’s a management theory that teams go through four stages: forming, storming, norming, and performing. I’d say we’ve truly gone from storming to performing in the relationship between engineering and product.

So, what is TimeTrace?

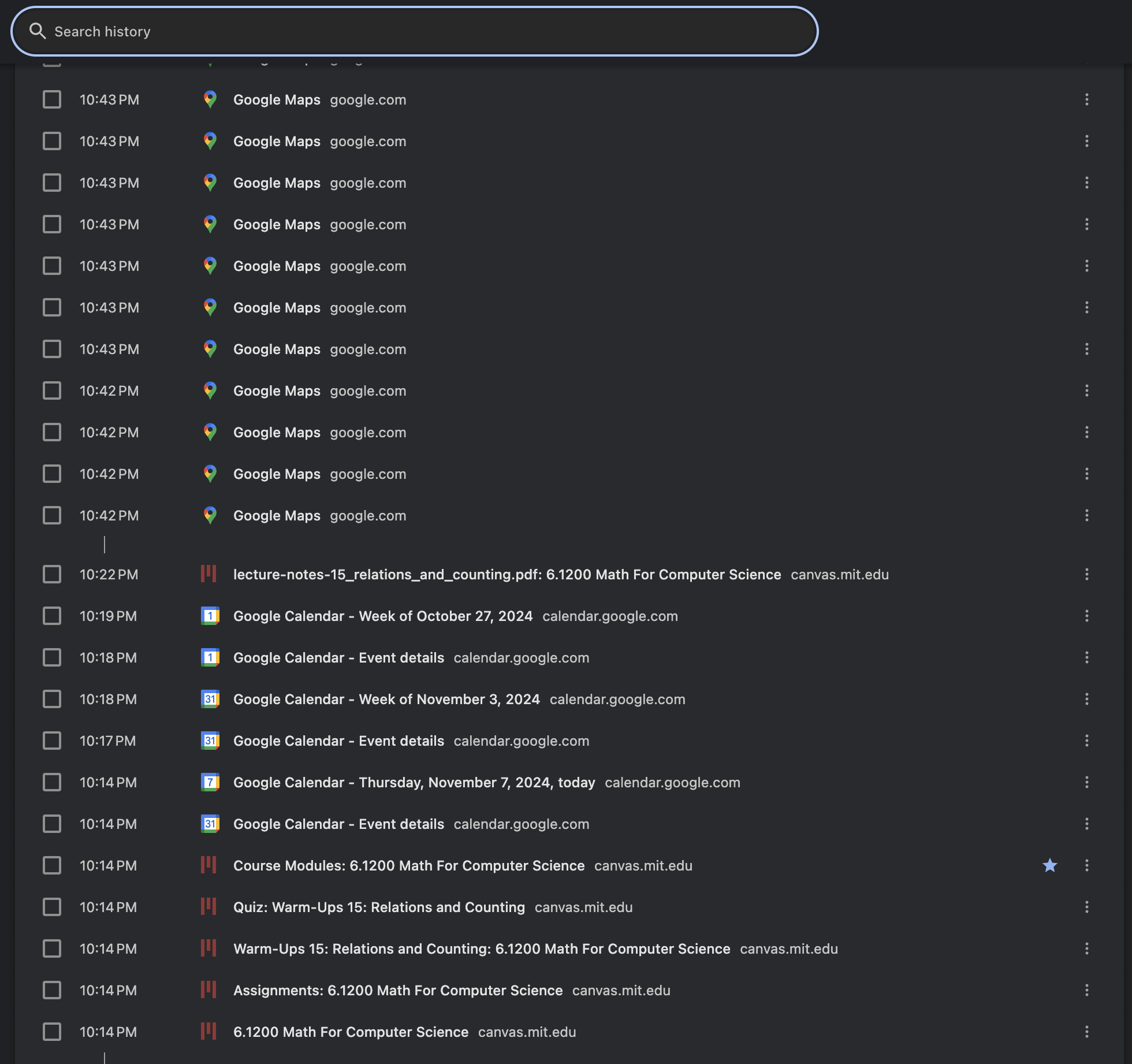

Imagine this: you’re trying to find a webpage you visited days ago. You open your browsing history and scroll endlessly but still can’t find it. You try searching with keywords but have no luck. Frustrating, right? This is what your browser history probably looks like:

The default Chrome browsing history has a few issues:

- Poor search functionality—it often fails to find what you need.

- It’s cluttered, with too many repeated entries for each page.

- It only saves 60 days of history.

- For older history, you have to scroll endlessly.

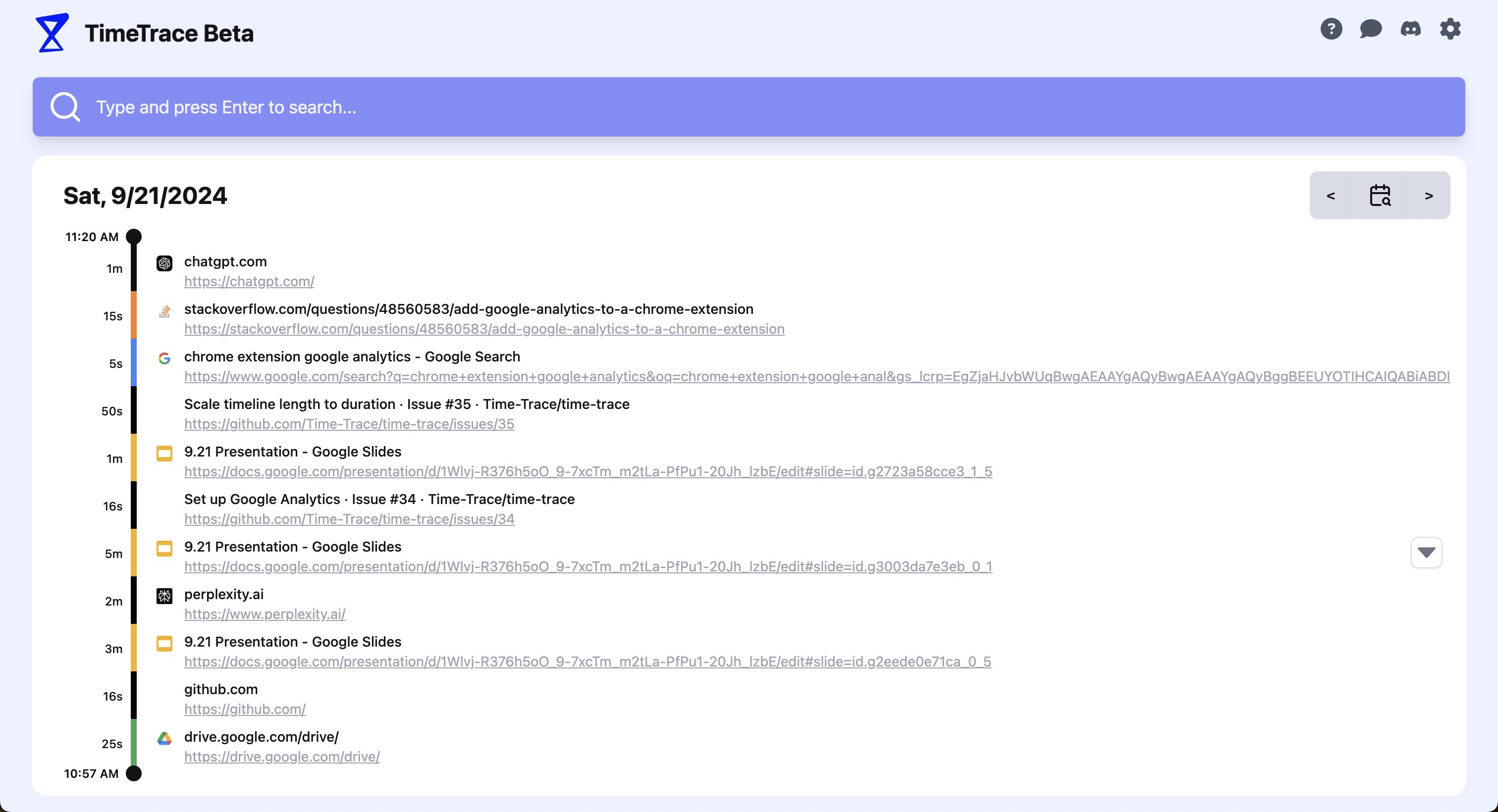

After countless failed searches, I decided to make something better. When I open my history, I want it to look like this:

This is TimeTrace—a more user-friendly browsing history. It offers:

- Full-text search for websites you’ve visited. Unlike the default history, which only searches titles and URLs, TimeTrace lets you search any keyword from the website’s content.

- Collapsed entries for sites on the same domain. If you read 50 chapters of a novel or flip through 200 slides, only one entry shows up (expandable anytime).

- Saves all history from the time of installation (and existing history before installation).

- Jump to any day’s history with a date selector.

TimeTrace is a Chrome extension that enhances your browsing history. It’s available for free on the Chrome Web Store, or you can visit our website: timetrace.ai, where there’s a download link.

We genuinely invite you to check out our project! Our team is continuously working to roll out new features to improve user experience, and we welcome feedback.

Thank you to my teammates for their contributions to TimeTrace and their feedback on this article. Could not have done it without you all!