A Leash of My Own

I have found salvation on the sidewalks of New York.

2024-12-01

NEW YORK, August 13, 2023, 2:45 PM – In a city known for strange sights, today’s scene along the Hudson took even jaded locals by surprise: a young man was spotted calmly walking a banana through the Financial District, tethered by a data cable, an accessory that was arguably more Ethernet than ethical. Passersby marveled at the quiet defiance in his unusual stroll. It turns out this wasn’t a TikTok challenge or a publicity stunt—just a personal journey of self-conquest…

An Old Mental Trick

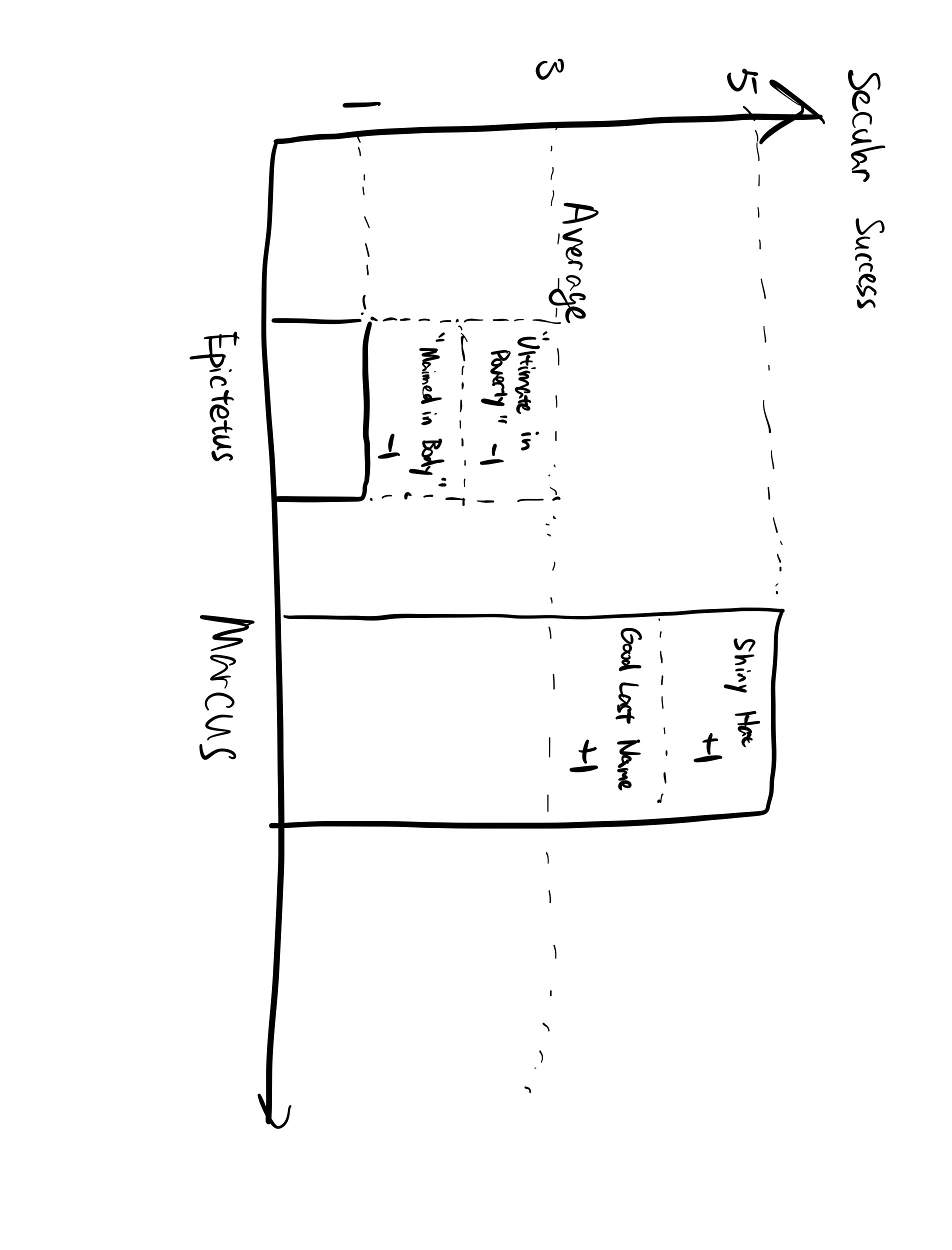

Picture this: two men, Epictetus and Marcus. Both devoted themselves to the study of philosophy, yet their lives could not have been more different.

Epictetus was born a slave. His legs were broken by his master. He had no possessions and was eventually exiled to some far-flung island. In his own words, he was “maimed in body” and “ultimate in poverty.”

Meanwhile, Marcus was the Roman Emperor, blessed with wealth, influence, and a truly fabulous last name. (And a shiny hat. Let’s not forget the shiny hat.)

If you were Epictetus, how would you feel about Marcus?

Let’s be honest—I’d feel unfair. By the metric of secular success, no amount of effort would allow Epictetus to compete with Marcus.

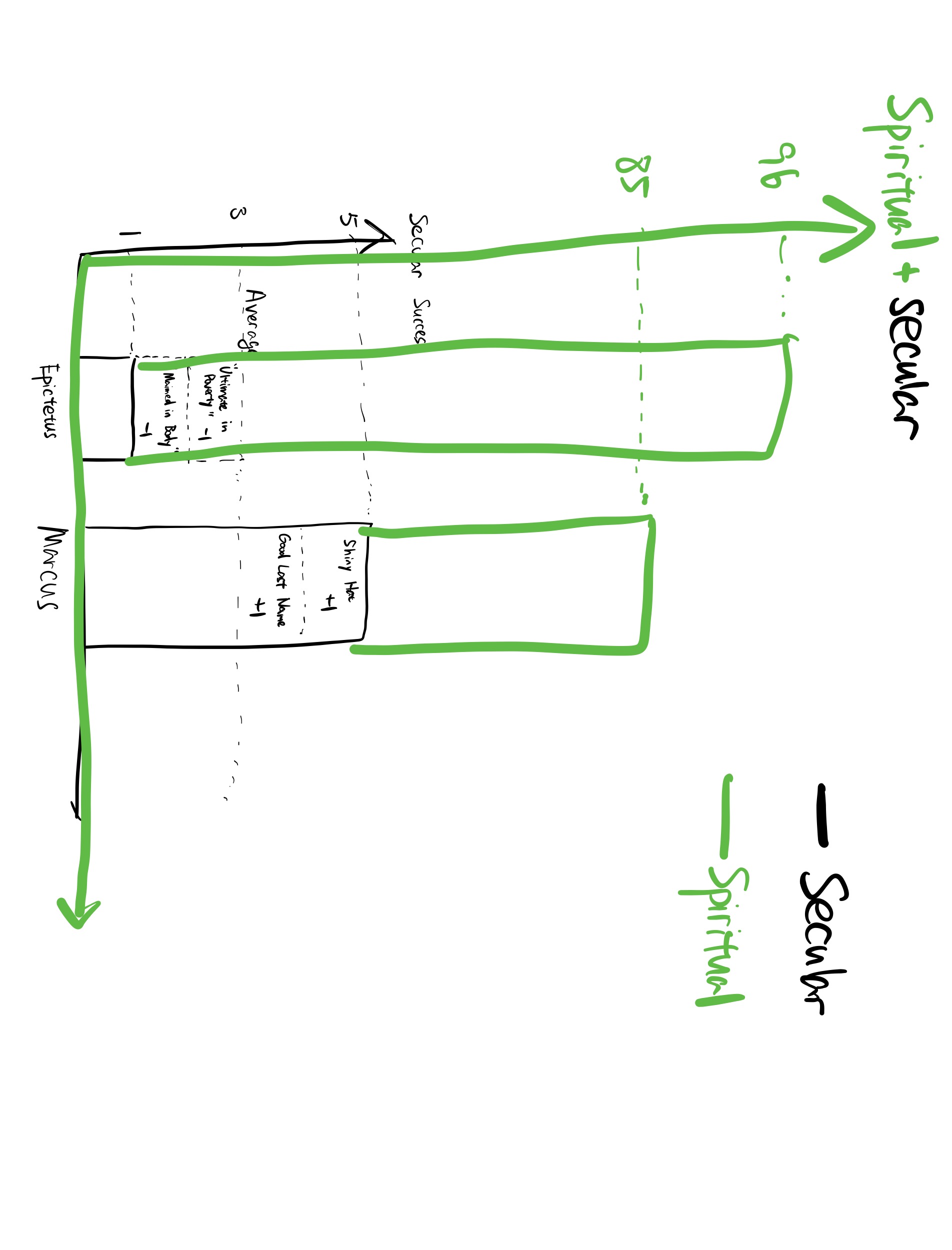

But Epictetus wasn’t a man to despair. Enter Stoicism, the philosophy that turns the worldly scoreboard on its head.

In the Stoic view, the only score that matters is virtue—an internal metric immune to external circumstances. Secular success operates on a scale of 1 to 5; virtue, Epictetus might argue, deserves a scale of 1 to 95, with perfection sitting pretty at 100.

And here’s the twist: on this new scale, Epictetus, the maimed exile, has a fighting chance to outrank the Emperor.

If I were Epictetus, I’d feel better already. It’s not just about scoring higher (though, let’s admit, that part is sweet). It’s about playing a game where the rules reward effort and internal growth, rather than starting positions or inherited wealth.

If I were Marcus, I’d feel invigorated too. Sure, I’m the Emperor of Everything, but if I want more material pleasures, I probably have to do drugs. With virtue, however, there’s always room to level up.

So, which worldview would you choose? The secular view, with its fixed leaderboard, or the spiritual one, where your ranking is about how much effort you put in?

I don’t know about you or Marcus, but if I were Epictetus, I’d pick the spiritual view.

And that’s exactly what he did. On his epitaph, Epictetus writes: “Here lies Epictetus, a slave, maimed in body, ultimate in poverty, and favored by the gods.”

Now, I’m no Stoic sage, but I’ve found my own life improved by adopting a higher value—my personal notion of “God.” Let me explain.

If My Highest Value is Myself…

During my last summer internship, I found myself trapped in an exhausting loop of self-comparison.

My fellow interns were both technically talented and socially adept. When I was next to them, I felt small. I was a small fish in a big pond.

This sense of inferiority was quite discouraging. Instead of pushing me to spend more time with these inspiring people, it made me want to retreat into my own little bubble. Being around them highlighted all the ways I felt inadequate, even though I knew, rationally, that their presence was an opportunity for growth.

Ray Dalio writes in Principles that he sees life as a series of ascending to higher and higher levels of play where the games get harder and harder. If I allowed my happiness to depend on how I measured up to those around me, I’d be setting myself up for an emotional rollercoaster, with every level-up bringing fresh turmoil instead of joy.

Here’s the problem: this instinct to compete, to measure yourself against others, is hardwired into us. Evolutionary psychology suggests it stems from ancient survival pressures—back when resources were scarce, and you had to outdo others to secure your status in the tribe.

But this primal instinct doesn’t map well to the world we live in now. Today, when you’re doing well, you’re often “promoted” into a larger tribe—a bigger pond with even bigger fish. And then there’s social media, which constantly dangles a curated highlight reel of people you’ve never met, all of whom seem to be living impossibly perfect lives.

If we keep acting as though success is a zero-sum game, where someone else’s win is our loss, we set ourselves up for perpetual dissatisfaction.

This realization forced me to rethink my values. Instead of tying my happiness to short-term achievements or my relative ranking to those around me, I decided I needed to base it on something higher. Something internal.

I decided to shift from what I call a “secular view”—focused on immediate outcomes and comparisons—to a “spiritual view,” one that prioritizes long-term growth and inner stability. My ups and downs must matter less. Instead of letting my million-year-old brain steer the ship, I must anchor myself to a higher value, my own faith.

In Search of a Higher Value

So, what should that higher value be?

This wasn’t a decision to take lightly. Choosing a higher value feels a bit like granting someone root access to your brain. I didn’t want to adopt a pre-packaged belief system from an existing religion. While Buddhism or Christianity have brought profound meaning to many, their values often come as bundles, with historical and cultural elements that don’t always align with today’s socio-cultural landscape.

Instead, I wanted to handcraft my own belief system, tailored to my life. I needed a value that wouldn’t come to me naturally but had consistently led to better decisions and greater happiness whenever I’d practiced it.

And surprisingly, that value had been hiding in plain sight. It’s so obvious that it feels almost embarrassing to formalize it. But as I’ve learned, sometimes the most obvious truths are the ones we need to spell out for ourselves.

The value I decided on is rationality.

When I told a friend about this, they didn’t understand asked:

“So you, too, are becoming a slave to productivity?”

I get why they said that. Rationality often gets a bad rap—it’s seen as cold, robotic, even dehumanizing. But that’s not how I see it. To me, rationality is a deeply practical tool. It’s about making predictions about what would be good for my life in the future and to guide my decisions in the present. It’s about balancing short-term discomfort with long-term fulfillment.

Let me give you an example of how I used rationality to make a decision that most people might find… well, bananas.

To Walk a Banana Rationally

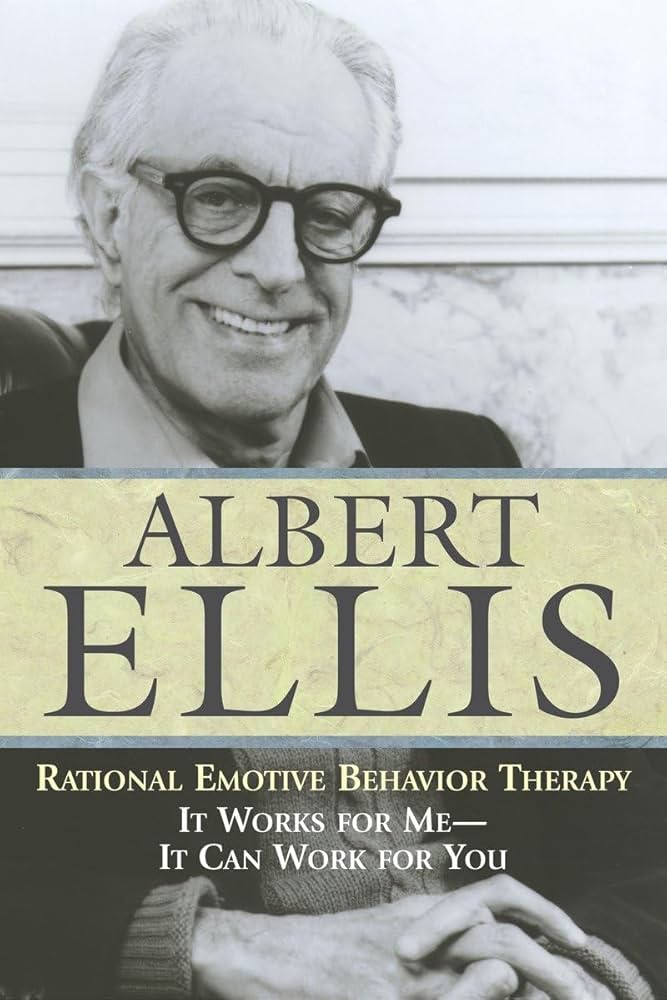

This summer, work was stressful, and I found myself diving into self-help books and therapy readings to unwind. That’s how I stumbled upon Albert Ellis, the charismatic guru behind Rational Emotive Behavioral Therapy (REBT). Ellis had this infamous homework assignment for socially anxious clients: walk a banana in public.

At first, it sounds ridiculous, which is precisely the point. The exercise pushes you to confront your fear of judgment and prove to yourself that the world won’t end just because you do something a little strange. As a naturally shy person, I found the idea equal parts terrifying and genius. So, one hot afternoon, I promised myself: today, I am going to walk a banana.

The plan seemed simple enough—until it wasn’t.

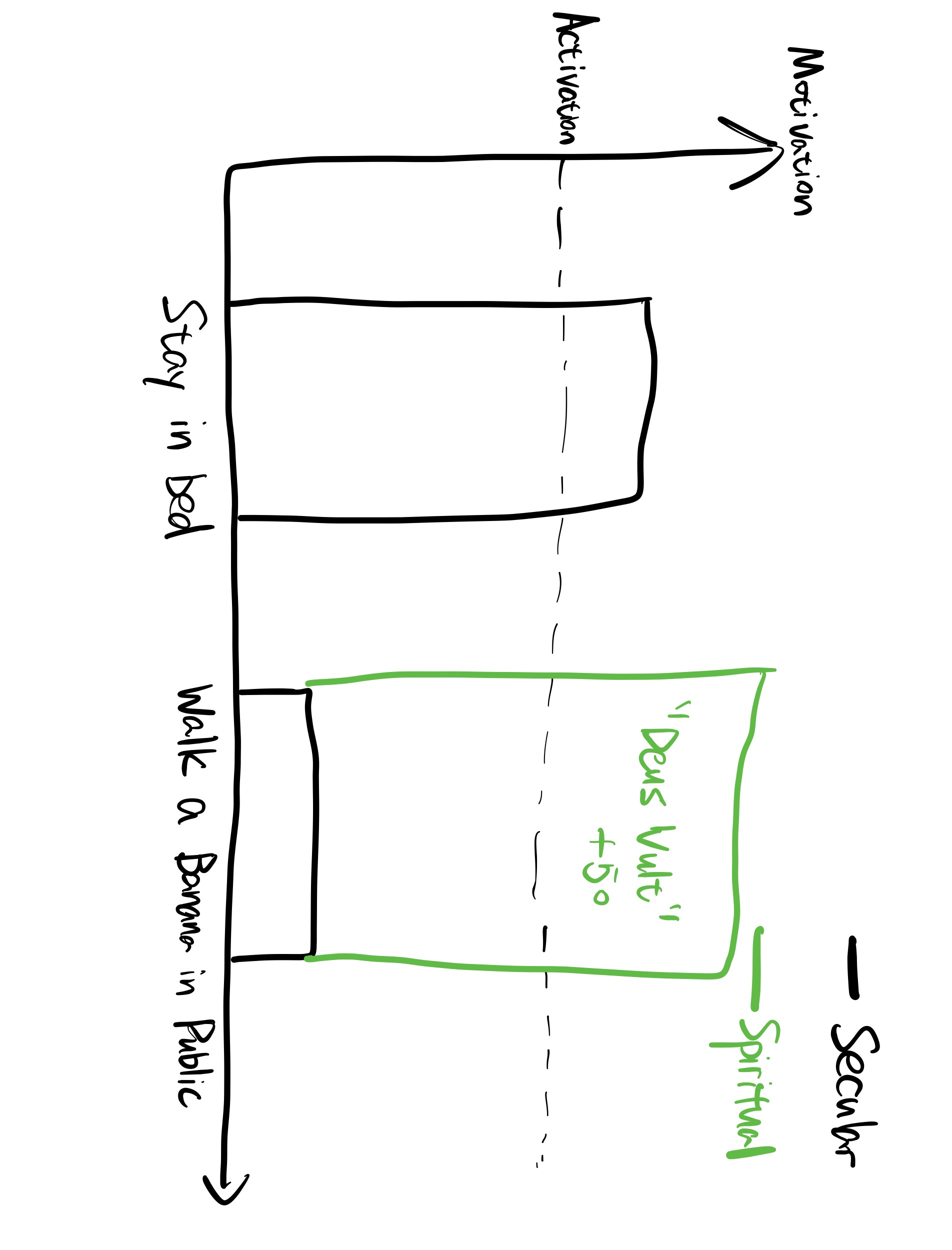

As the appointed hour arrived, my anxiety hijacked my brain. Suddenly, my bed felt softer than ever, the summer heat more oppressive, and the thought of walking a banana completely absurd.

I stood there holding the banana, now leashed with a long HDMI cable (because, as a tech guy, I lacked more traditional leash options), but I couldn’t make my legs move.

I was about to give up when I remembered my newly adopted value: rationality. Surely, if ever there were a moment to test its guiding light, this was it.

I broke the situation down. Rationally speaking, walking the banana would likely have no negative consequences. At worst, I’d give a few strangers a funny story to tell. At best, I’d boost my confidence, create a memorable experience, and prove to myself that I could override my fears. On the flip side, if I backed out, I’d reinforce the belief that I lacked courage—the very thing I was trying to change.

The pros outweighed the cons by a landslide. In my mind, the verdict was clear: Deus vult. God wills it.

I thought about Daniel Kahnemann’s distinction between System I and System II. Here, System I—the reactive, emotional part of my brain—was freaking out. It saw this exercise as a threat to my tribal status, an ancient instinct from a time when standing out could be dangerous. System I screamed, Stay in the cave!

But System II—the rational, deliberate part of my brain—knew better. I wasn’t in a prehistoric tribe; I was in New York City. The strangers I passed would barely register my existence, let alone judge me in any meaningful way.

And so, I commanded my legs to move. They carried me—hesitantly at first—out of my room, into the elevator, and onto the bustling streets.

Two hours later, I returned triumphant.

The New York crowd embraced the absurdity with open arms. My apartment front desk clerk asked if he could pet the banana. I introduced it as “Cavendish” to a gardener on the street and struck up an impassioned conversation about banana rights and the conditions of industrial farming. Near the 9/11 memorial, a tour guide gleefully informed his group, “You can see all kinds of weird people in New York!” He turned to me and interviwed why I was doing this.

“Social anxiety,” I replied.

He nodded sagely before turning back to his group. “Social anxiety! That’s the one thing you do not need in New York.”

This experience crystallized something important for me: rationality isn’t just about doing “productive” things. It’s about using reason to push past in-the-moment fears that don’t serve your long-term goals. It is about becoming the person I want to be.

The Emotional Benefits of Rationality as a Religion

Adopting rationality as my guiding value didn’t just change how I acted—it changed how I felt. After all, a good religion should offer not only rules for behavior but also a sanctuary for the soul.

When I first decided to “craft” my religion, it was because I didn’t want my sense of self-worth to depend on how I ranked relative to the people around me. That mindset had led me to avoid people who were better than me in some way. I’d distance myself out of insecurity, missing out on opportunities to grow.

But with rationality as my religion, I can see these people differently. Instead of competitors, they become my “rationality priests,” offering sermons from which I can learn. If they’re further along the path, isn’t it natural that I’d be their pupil? This mindset makes me much more comfortable to interact with them.

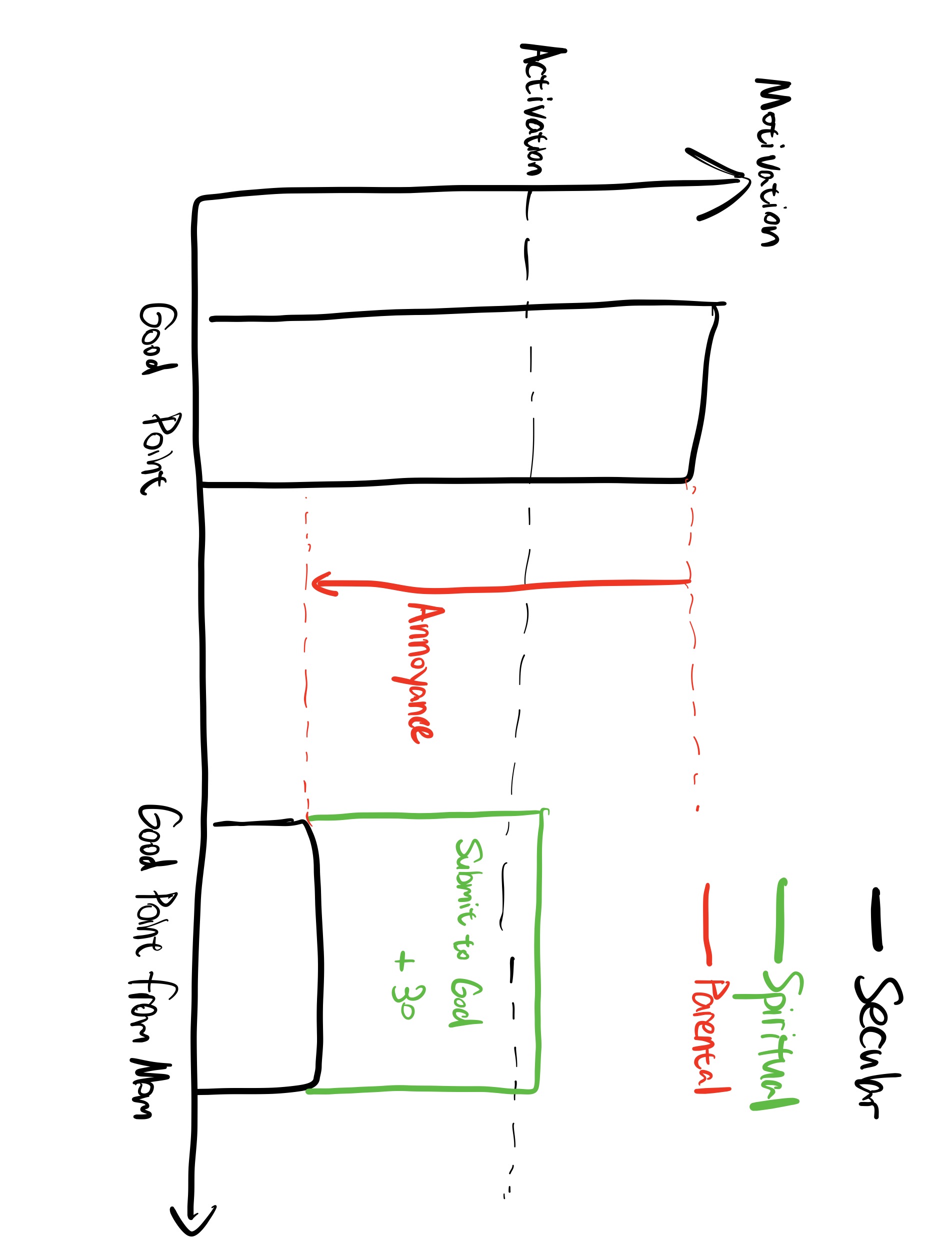

Rationality also helps me deal with moments when my emotions flare up against reason. For example, when my mom gives me unsolicited advice about my life, I often get annoyed because it feels like she’s undermining my independence. Even when she’s right, I’d sometimes reject her points just to assert my autonomy.

But with rationality as my higher value, I realized I don’t need to see it as “submitting to my mom.” Instead, when I accept her good points, I’m not bowing to my mom—I’m bowing to my God, which feels a lot easier (and much more dramatic, honestly).

Arguments Against Rationality as Higher Value

Of course, not everyone sees rationality as a good thing. Some people argue it’s too cold, that leaning on rationality means “killing a part of yourself”. I used to worry about this too. I’d hear the word rational and picture people suppressing every ounce of human emotion and not really living.

But then I realized something: our feelings aren’t always the best parts of ourselves. Take the example of reaching for your phone to open that app—the one you know isn’t adding much to your life. Is that really you reaching for it? Or is it just your brain, manipulated by bright colors, dopamine, and a well-tuned algorithm? Deep down, you might genuinely prefer spending that time with a friend or reading a book, but your feelings are being hijacked.

Therapists know that humans tend to regard whatever they feel most strongly as the truth. For example, someone struggling with depression might feel worthless—and because the feeling is so intense, they assume it’s objectively true. But with the right support, they can develop a different belief—one just as strong, but far more empowering.

This is why I don’t think all feelings are sacred. They’re evolutionary leftovers from an ancient operating system, designed for a world that no longer exists. As a programmer, I’d call them “legacy code.” Or, to be less polite, “shit code.” It’s clunky, written for a long-forgotten set of requirements, and no one has any idea how to refactor it. So while feelings can be valuable, I’d hesitate to glorify every impulse just because it’s “natural.”

Rationality doesn’t mean ignoring feelings altogether. It means taking a step back and deciding which feelings deserve your trust. Not every ping from your brain’s million-year-old computer is worth acting on. And honestly, learning to debug your mind is one of the most liberating skills you can have.

Conclusion

After all this talk of rationality, I have a confession to make: I’m not a particularly rational person. Compared to the STEM-heavy people in my life, rationality often feels like an afterthought for me.

You see, I love the irrational. My natural instinct is to gravitate toward the artistic, the spontaneous, the absurd. I enjoy theater, with its flamboyant embrace of humanity’s messy contradictions. I revel in madness, the kind that feels alive and untamed.

This is why I don’t—and can’t—stay rational all the time. Nor should I. There’s immense power in irrationality, especially when it comes to connecting with other humans. Humans are gloriously irrational creatures, and much of what we cherish in life—friendship, laughter, love—thrives in the spaces logic cannot reach. Viktor Frankl didn’t survive the horrors of a Nazi concentration camp by relying purely on rationality. He drew strength from something deeper, something more illogical—a kind of hope that defies calculation.

This is why I only invoke rationality in moments that matter deeply—moments that could shape the trajectory of my life. For instance, when crafting the values of “Andi’s religion,” I turn to rationality as my north star. But after all, Most decisions aren’t life-altering. 20% of your choices create 80% of the impact. For example, when I’m hanging out with friends or enjoying a lazy afternoon, I’m perfectly happy to let irrationality run the show.

Here’s the thing: I’m not trying to sell you rationality. I didn’t adopt it as a higher value because it’s inherently superior or noble. I chose it out of practical necessity—because it balances my nature, helps me course-correct, and offers a framework I can lean on when life feels unsteady.

Also, rationality is more of a “how” than a “why”—a means, not an end. If my religion were a cathedral, rationality would be the scaffolding: useful for building something meaningful, but never the thing itself. I’m still searching for my ultimate “why.” Right now, I’m leaning toward something like “love”: love of life, love of knowledge, love of the people I care about. Love feels less like scaffolding and more like the cathedral’s stained glass—a vision of what could be.

What I’m really advocating for isn’t rationality specifically—it’s the idea of having your own higher value. Some people hesitate to adopt one, fearing it will take over their lives. But here’s the truth: you’re always subject to some value, whether you choose it consciously or not. If you don’t decide what guides you, short-term desires will. And those desires? They’re often planted by others—advertisers, algorithms, the noise of the world—pulling you away from your long-term goals.

On your own, it’s hard to resist those desires. That’s where a higher value helps. When I didn’t want to walk the banana, it was because my short-term instincts craved safety and comfort. On its own, my brain wasn’t going to convince me that two hours spent walking a banana through the streets of New York would be better than two hours in my cozy room.

But with my personal religion, I could borrow the long-term satisfaction I knew awaited me and use it to override the short-term resistance. Walking the banana became more than a silly task—it became a pilgrimage:

“I walked the banana not for earthly praise, but for liberation from System I’s tyranny. I bring home not a mere decayed fruit, but Cavendish, bound with the Cable of Data, a crown woven of rational thorns. I have found salvation on the sidewalks of New York.

Blessed are those who embrace the absurd in pursuit of self-conquest, for they shall walk in the light of their own choosing.”