Andi Versus LLM

Four years ago I wanted to do machine learning. Now, I am no longer sure.

2023-6-25

Zero

My response at the time was that poetry is useless, just like the peacock’s feathers. But the female peacock prefers male peacocks with beautiful, colorful tails because it shows the male’s capabilities: being able to flaunt such costly feathers in front of predators and still survive to this day surely means something.

Similarly, those who are idle enough to study how to rhyme in speech are either of extraordinary birth or exceptional ability, both of which make them quality partners. Thus, the genes for poetry continue to be passed down.

What area in Computer Science do I want to do?

Four years ago, I would have definitely said machine learning.

I remember one winter afternoon in my sophomore year of high school, after lunch, I walked into an empty classroom to discuss my RSI summer school application essays with my advisor. I wanted to write about this amazing thing called machine learning.

Back then, I had only learned a tiny bit about machine learning in the school’s computer lab, but I was utterly convinced that artificial neurons could surpass human intelligence through the iterative learning process of calculus and linear algebra.

I even thought that neural networks could be considered humans, deserving of human rights, because what we pride ourselves on as intelligence is nothing more than the activation and suppression of neurons between the zeros and ones; the principle of learning is that more frequently used neural pathways become thicker while the lesser-used ones gradually fade away.

Our cognition, emotions, and behaviors are formed through such simple mechanisms over years of evolution, learning, and iteration. Why should we think we deserve more rights than neural networks?

My advisor asked me to explain my ideas for the summer school essay. To illustrate the idea, I thought I must explain the math behind gradient descent, so I began to draw on the blackboard.

In the middle of this, a humanities student who also wanted to discuss summer schools with the director came in but politely sat down to listen. When I was talking about how human civilization was just a result of iterative evolution, she raised a question: “If all of human civilization can be explained through evolution, how do you explain poetry?”

My response at the time was that poetry is useless, just like the peacock’s feathers. But the female peacock prefers male peacocks with beautiful, colorful tails because it shows the male’s capabilities: being able to flaunt such costly feathers in front of predators and still survive to this day surely means something.

Similarly, those who are idle enough to study how to rhyme in speech are either of extraordinary birth or exceptional ability, both of which make them quality partners. Thus, the genes for poetry continue to be passed down.

The humanities student nodded.

I went from mathematics to computers, from computers to biology, and from biology to philosophy. When I finally finished, the director said, “Very good. Write it down and show me the essay.”

When I left the classroom and looked up at the sky, it was dark already. I had been talking for four hours.

I was not admitted to RSI. However, I remember the high school me, knowing basically nothing, orating about machine learning for four hours straight. I remember the surprise I felt when I stepped out and saw the starry sky.

I thought that was what passion meant. I thought machine learning was my passion.

One

Now at MIT, after taking so many AI classes, I can no longer talk for four hours.

My sophomore fall I took the NLP (Natural Language Processing) class. The last lecture was on the future of NLP. The professor added some new slides last minute, mentioning there is this new language model called ChatGPT, from OpenAI, the small company who also created GPT-2 and GPT-3. He said the model looked quite impressive.

I checked it out right away, and indeed, it was impressive. I had studied language models for a semester and had seen all kinds of incomprehensible outputs, but it looked like this new language model did not suck. It output coherent English sentences.

The rest is history. Not only did it handle over a hundred languages fluently, it wrote code, poetry, and emails better than I did. The world finally saw the power of machine learning, neural networks, and NLP. I realized it had truly gone viral when even people unrelated to computing began posting about ChatGPT and OpenAI.

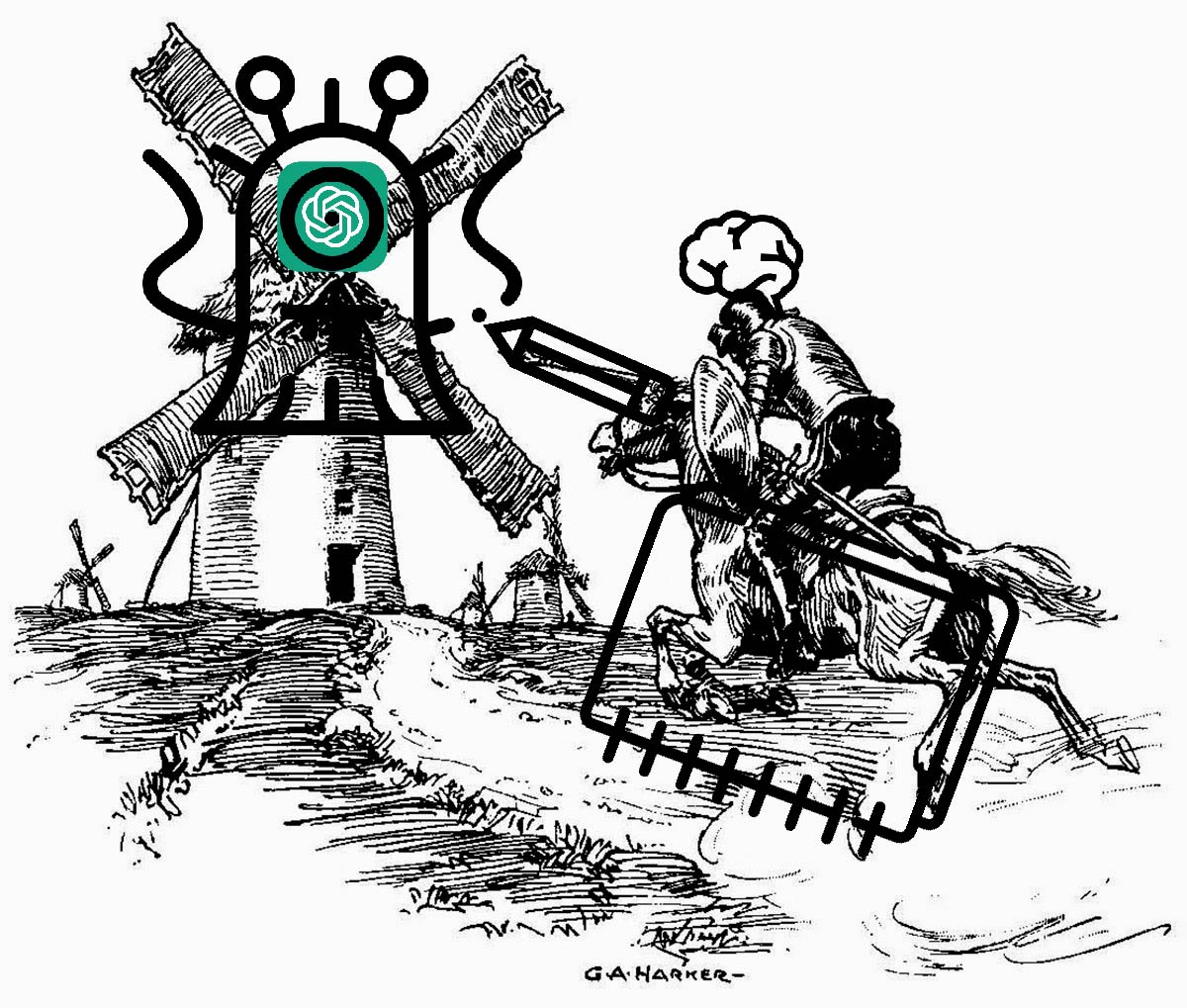

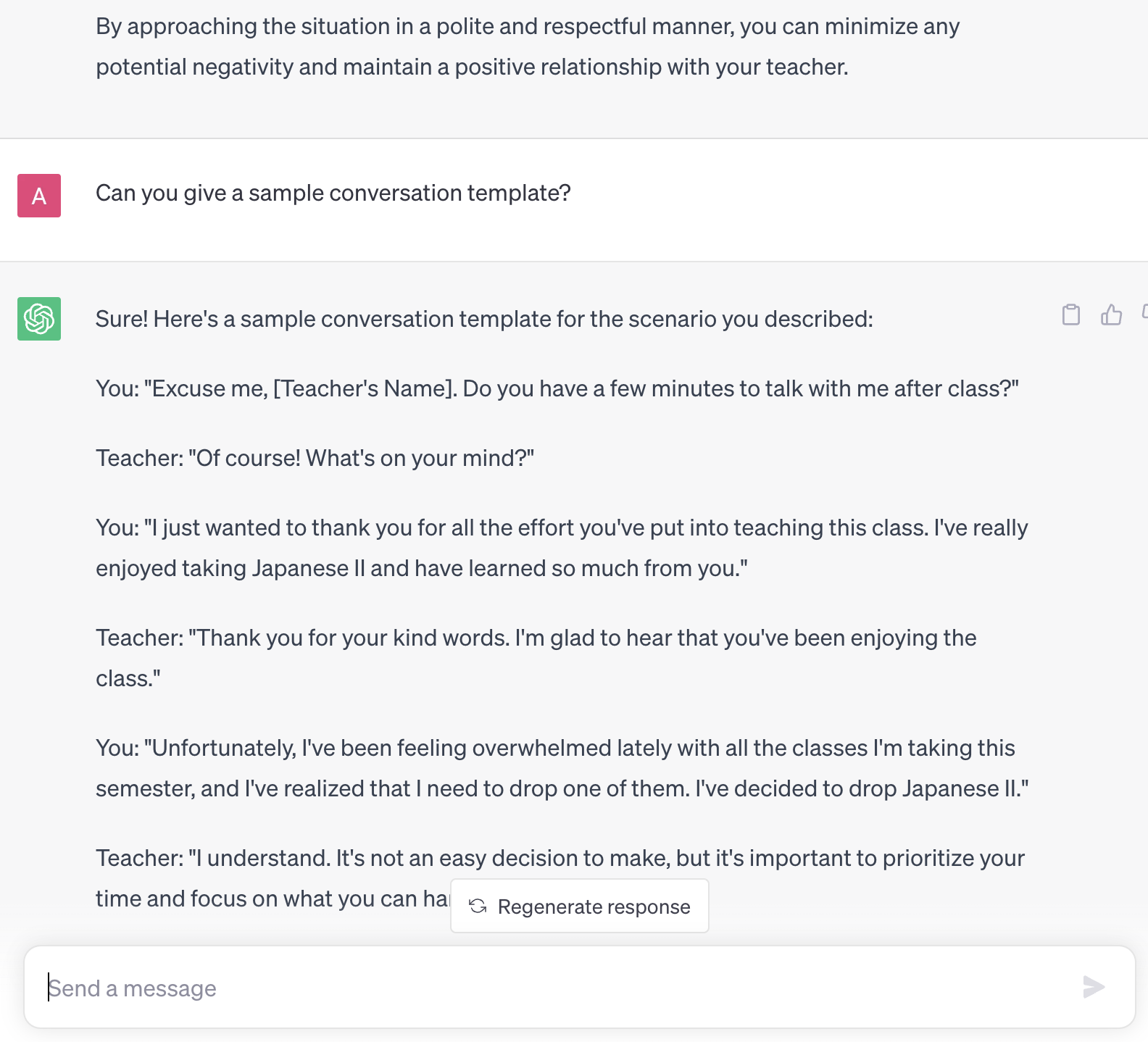

For many, it was just a more interesting chatbot, but for me, it became my right-hand man. It proofread all my emails, explained slang I didn’t understand, and even helped me rehearse dialogues before I told a teacher I wanted to drop a class.

A few days ago, I came across a term from an article by my friend Mingyang Deng called “big model monster.” I think it captures the essence of large language models very well. It’s “big,” it’s a “model” of language, and while its way of thinking seems very different from humans - just a bunch of matrix multiplications and nonlinear functions stacked together - it talks like a human, so it’s “monstrous.”

It felt like we were making Frankenstein.

Two

Eventually, humanity will be like a peacock, flaunting its costly self-esteem, pretty but otherwise useless. We’ll all become like the peacock’s feathers, like poetry.

Last semester, at a lecture, I met a classmate I hadn’t seen since orientation. He asked me if I was still advocating for robot rights.

He had been indifferent when he first heard me talk about it, but now he had become a dedicated researcher in reinforcement learning - he wouldn’t take any classes unrelated to machine learning.

When I heard my old passion, a mix of emotions swirled within me, and I smiled bitterly, “They don’t need me to advocate for robot rights.” Everyone had piled into machine learning, adding me wouldn’t make much difference.

I said it with a smile, but anxiety still led me to look for machine learning opportunities at MIT, to no avail. (If you know of any good opportunities, please let me know)

When I didn’t know at the time was that, all the research opportunities that don’t say machine learning actually need you to do machine learning, and all the ones that say machine learning don’t want you to do the machine learning part - they just want you to handle the data.

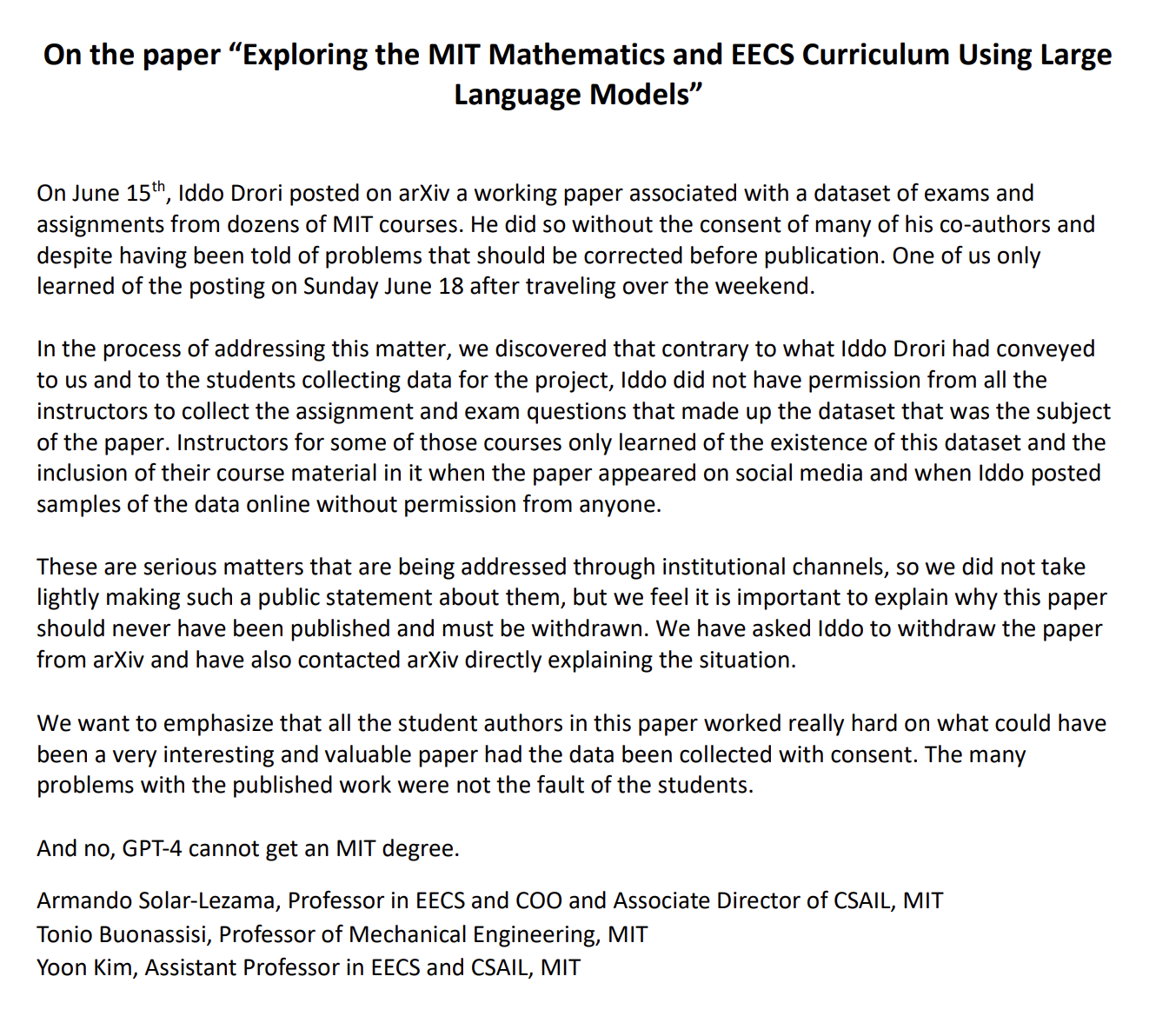

I searched on Elx and had several interviews, none of which particularly satisfying. One interview left a particularly deep impression because the project involved proving that a large language model could earn an undergraduate degree from MIT. I showed up with my resume filled with machine learning experience, and the first question the guy asked me was:

“How well do you know physics?”

I didn’t expect my physical capabilities to be relevant. “I’m preparing for the 8.02 electromagnetism ASE exam this winter break. If I pass, I’ll meet the MIT graduation requirements.”

His eyes lit up at the mention of electromagnetism. “Can you grade electromagnetism problems?”

“Huh?”

“Specifically, having ChatGPT solve problems, and you grade them. 0 is wrong, 1 is right, 0.5 is half right, put it in this spreadsheet. Can you grade all the psets for an advanced electromagnetism course?”

I thought he had some sophisticated method based on his project description, but it turned out to be a rough assessment. Me grading advanced electromagnetism would result in garbage in, garbage out. I saw other subjects on the spreadsheet and said, “I’m more confident about other courses; the data quality would be better.”

“Those courses have been claimed by others. Only these two are left now: electromagnetism and advanced algebra. Do you know advanced algebra?”

“No.”

“Then can you grade electromagnetism? Tell me yes or no.”

“I… If you give me some time to learn, with the help of Google—”

“—I’m asking if you can grade. We need it before the start of the semester. If you can’t do it, I’ll find someone else.”

Learning to grade such problems to a satisfactory standard would mean I’d give up my winter break. But I figured undergraduates definitely get the dirtiest and most tiring jobs. Maybe I need to lower my expectation.

“I can do it, but I need to know what the project entails afterward; you can’t just have me doing grunt work.”

“Don’t worry, the later work is very interesting. There are about a dozen people working on this great project, and we are having a lot of fun, and we will only have more fun later.”

“What exactly is it?”

“You’ll find out in time. We’re sitting here talking, and you can still confirm I’m human, but what about later? Can you still be sure that the person talking in Zoom is a flesh-and-blood human? General Artificial Intelligence (AGI) is just around the corner, and you are still squabbling over your little time committment. You have no idea what you’re missing out on!” (not verbatim)

I couldn’t help but feel ashamed of my shortsightedness. But I really didn’t want to give up my last few days of winter break without knowing what I’d be doing later.

“I’m sure the project you’re talking about is very interesting, and I understand the future of AI is very promising, but unless you clarify exactly what I’m supposed to do, I can’t convince myself to commit too much time and effort to this project.”

“Ha,” he scoffed, “I advise you to leave all this diplomacy and game theory to AI; they’re already better at this kind of stuff.” He was referring to a recent incident where an AI named Cicero topped a diplomatic game called Diplomacy.

The conversation had become quite unpleasant. I said, “Thank you, if I change my mind, I’ll come to you.”

“No, you don’t call me. I call you. Understood?”

“Understood.” I ended the video call, feeling as uncomfortable as if I had swallowed a fly.

I think this project, built on the sweat and tears of undergraduates, illustrates the cost of some machine learning projects: while machines become more human-like, people become more machine-like.

It has removed “how humans think” from the scientific creative process, focusing instead on how many GPUs you have, how many billions of parameters. It is like making noodles, adding more water if the flour is too dry, more flour if it’s too wet, repeating experiments until one day, you perform 1% better than someone from a year ago, and you can proudly publish a paper.

What bothers me the most is that discoveries are equally difficult for everyone, but everyone keeps grinding, not wanting to miss the chance to create the next big thing. But statistically, each person is unlikely to achieve it. And once someone develops AGI, all other efforts will have been in vain, meaningless.

Eventually, humanity will be like a peacock, flaunting its costly self-esteem, pretty but otherwise useless. We’ll all become like the peacock’s feathers, like poetry.

Three

During my summer internship, the company wanted us to rank our interests in different technologies to do team assigment. I placed machine learning in a medium position. As a result, I was assigned to a frontend team in the Cloud Engineering department. I later heard that over two hundred interns were assigned to the machine learning department.

My mom, who knows nothing about computers, was secretly disappointed when she heard I hadn’t chosen machine learning. Similarly, in my roommate’s opinion, not placing machine learning first was a big mistake.

Roommate: “My manager works remotely, we hardly ever see him, and our project has hardly any guidance. They just say, ‘Here’s the data, predict whatever you want.’ (Makes a regretful face) But I think I’m still very lucky. After all, I was assigned to machine learning. I have a classmate who published two machine learning papers and ranked machine learning first on his interest form, but he still wasn’t assigned to machine learning and got sent to do frontend instead. (Others chuckle) He’s even thinking of quitting the internship and running away.”

Roommate turns to me. “By the way, Andi, what does your team do again?”

Me: “Frontend.”

Specifically, I work on user interface (UI) design, which involves deciding how a website looks, how to layout, and where the buttons should be, among other things. Because it’s user-oriented, it’s called frontend, as opposed to the backend, which is primarily about implementing actual functionality.

He made a sympathetic face. “My condolences.”

The others nodded.

Me: “What’s wrong with frontend?”

The others then explained to me, as if imparting common sense, why they disliked frontend. Frontend is easy; people who don’t even major in CS can do it after just a few months of bootcamp. It lacks technical depth and influence; they spend all day discussing how to place buttons or whether moving them two pixels to the left or right looks better. The hardcore engineers care less about the foolish mistakes users can make, more about how to create the product, how to “make it work.”

But hearing their opinions left a bad taste in my mouth. It sounded like my job wasn’t considered smart, like it “didn’t match” the intelligence expected of someone with a formal computer science education.

But I actually quite enjoy thinking about how buttons should be placed. Every day when I write in my diary, I think about how to make information search more straightforward and visual, whether to center my drawings or align them to the left. I think backend tasks are too predefined: input this, output that, but the frontend involves a lot of creativity and requires many insights to do well.

And working frontend has other benefits too. My roommate works from 9-6. I work from 10-4. Every time my roommate comes home exhausted and collapses on the sofa after seven, I’ve already cleaned up the kitchen (my cooking skills have quickly surpassed my roommate’s). When he goes to bed at ten (because he has to get up after seven), I can still journal for an hour.

I comfort him with his values: “Everyone knows how useless my job is, so no one cares how long we work each day.”

I eventually realized why I, with no frontend experience, was chosen for this frontend team.

After a meeting, the tech lead said, “I remember seeing someone’s resume that mentioned work related to Fortnite (a video game). Who was that?”

I raised my hand. I had optimized Fortnite’s frame rate on AMD graphics cards during my internship at AMD, and it was written in the first line of my resume.

My boss also stopped his departure, turned back, and stood still. “I play Fortnite too. Can you tell us more?”

It turned out that was how my resume was selected. I guess there were too many words on it for him to bother reading, but this guy saw his favorite game mentioned in the first line and was immediately interested.

Maybe if I had put Minecraft in the first line, my summer experience would have been totally different.

Four

I see my struggle with whether to study machine learning as a battle with the “big model monster,” like Don Quixote’s battle with the windmills.

The big model monster doesn’t care whether I study machine learning; just like the windmill, it symbolizes inevitable technological progress.

While doing frontend, I came across a YouTube video about the best personality to become a UI/UX designer.

It said that the most important ability for a UI/UX designer is the ability to communicate with both technical and non-technical people, as well as a curiosity to understand the process a user goes through when using a product, a willingness to conduct Empathy Interviews to listen seriously, and to write down the other person’s thought patterns… I care about these things!

I’ve heard a theory that some people have powerful operating systems, while others have user-friendly interfaces — I’ve always aimed to be among those with powerful operating systems who have the friendliest user interfaces, and among those with friendly user interfaces who have the most powerful operating systems. In other words, the ability to communicate with both technical and non-technical people.

I’m always curious about what influences the way a user uses a product. Every time I pass a door, I wonder if it’s a door that people instinctively know whether to push or pull. I obsessively note down every point in long conversations with close friends, the other person’s thought patterns. I believe that “the medium is the message,” the way a product is presented is more important than the product itself.

Perhaps this job, looked down upon by “real” technicians, is just right for me.

And maybe someday, AI will be able to design any program, solve any math problem, and do every rational task we pride ourselves on better than us.

The only two things it can’t do are decide whether a button looks better moved two pixels to the left or to the right, because beauty is subjective, and understand and empathize with what a human feels and the foolish actions they might take upon seeing something.

By then, my advantage will be that I have many opinions about what is beautiful, and I am just as foolish as any other human. I can even cook tomato and eggs, and today’s robots can barely open doors, let alone cook.

I see my struggle with whether to study machine learning as a battle with the “big model monster,” like Don Quixote’s battle with the windmills.

The big model monster doesn’t care whether I study machine learning; just like the windmill, it symbolizes inevitable technological progress.

I’m different from Don Quixote because I clearly understand what the big model monster can do.

I’m neither a blind AI doomsayer nor an arrogant denier of AI’s capabilities. I know what it is - billions of neurons performing multiplication and addition; I know what it can do — write code and emails, spouting a bunch of empty platitudes; thus, I’m certain it will one day replace most people’s jobs, including mine. We will all become peacock’s feathers. We will all become poetry.

But I still charge at it with the ideals of the old world; this has nothing to do with technology. It’s about my character arc, about closure.