AI4PseudoScience

If intellectualism declines, can science be far behind?

2024-2-21

Part One

This semester, I am in two statistics classes: one from the Math Department (Intro to Statistics) and the other from the Computer Science Department (Intro to Statistical Data Analysis).

Though the content is similar, the teaching styles are vastly different.

The math department’s course is taught by a postdoc who meticulously defines, proves, and explains each theorem step by step.

In contrast, the computer science course is taught by a Russian professor who previously did machine learning at Amazon.

For him, it is not about right or wrong: it is about what is more “cool.”

“We’re calculating an eigenvalue here because it is a cool thing to do - even more cool if the matrix is symmetric.”

“Both of these estimators are cool. Plug-in is cool, but unbiased is also cool. It’s hard to say which one is more cool.”

Part Two

That is what cool people do. Be brave. Be fearless. Make me proud.

Turns out these “cool” statements are not just random. The Russian professor knows what he is talking about.

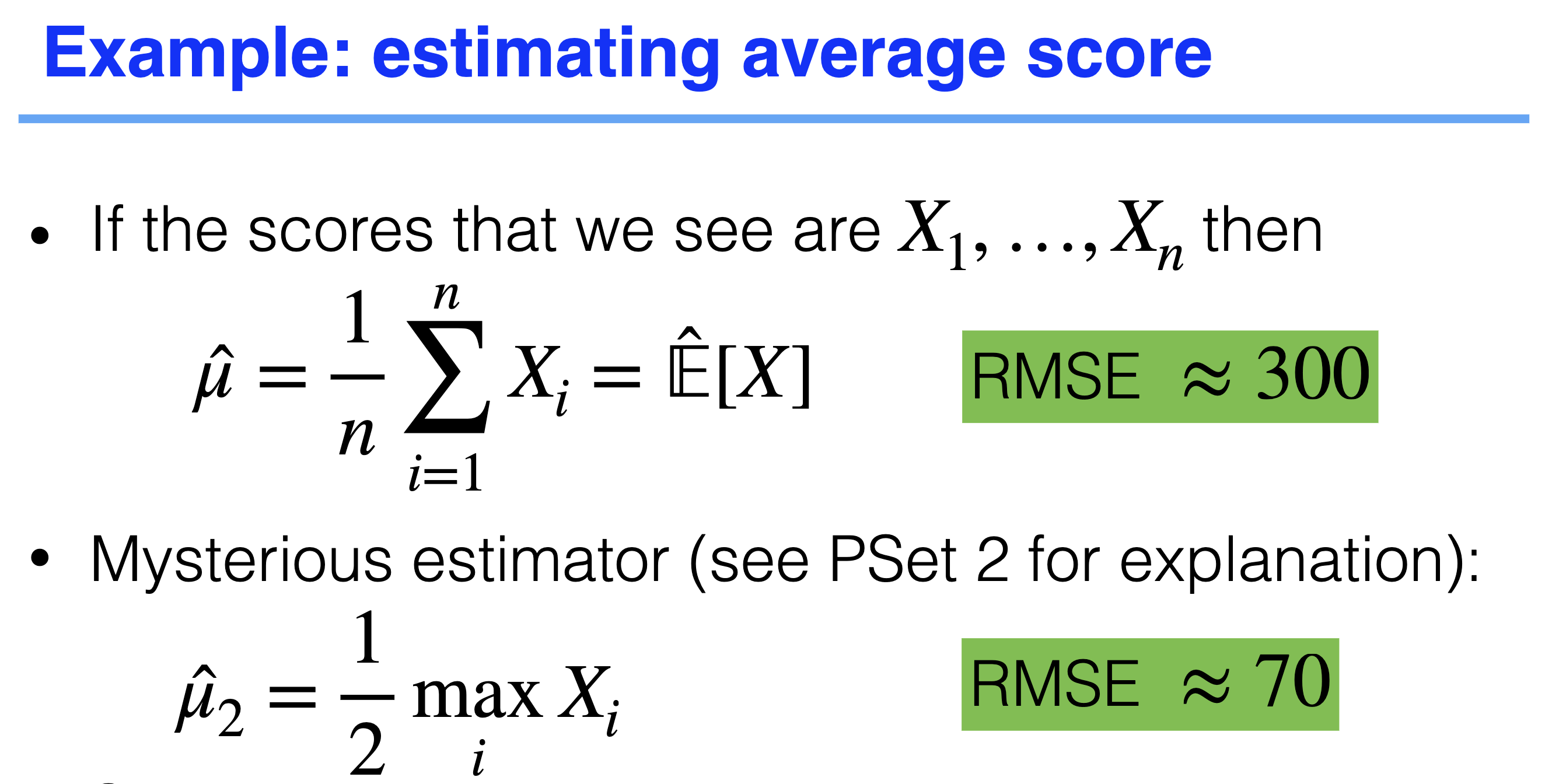

Once, he posed a problem: there are N balls in a bag (N unknown), numbered from 1 to N. You draw n balls (n is much smaller than N). How do you estimate the total number of balls in the bag?

His solution was to take the largest number from the drawn balls as the estimate for N.

He said this method was cool and that the British used a similar approach with German tank serial numbers to estimate the total number of German tanks during WWII.

Initially, I thought this didn’t make sense. Taking the maximum number would only underestimate N. This estimator is biased.

I thought a better estimator would be the average of all the numbers, which would be around N/2, and you double it to get N. The average would be an “unbiased” estimator, meaning that it does not tend to underestimate nor overestimate.

But it turns out his estimator of simpling taking the max, while simple and biased, has a lower RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error) than the unbiased estimator.

All models are wrong. Some are useful.

This Russian professor calls machine learning a “fearless method.” He often lauds the pragmaticism of fearless approaches that aren’t followed with any theoretical justifications. An example from the estimator lecture would be:

“The cool way to do plugin is that you never stop. Whenever you see a statistic about the true distribution, you add that little hat on top of the expectation and make it about the empirical distribution. That is what cool people do. Be brave. Be fearless. Make me proud.”

Part Three

We don’t need data scientists. We need data engineers.

The triumph of fearless methods of machine learning over traditional statistics is just a sign of the decline of intellectualism. Or maybe instead of decline, it would be regression toward the mean. Being useful has never been the primary goal of rigorous math and science anyway.

In the 20th century, we had the atomic bomb and semiconductors, and, for a brief period, science was productive. Turns out that was the exception, not the norm. Human has learned a bitter lesson: human knowledge is nothing compared to raw computational power.

That Russian professor says we don’t need data scientists. We need data engineers.

He pronounces “gradient descent” as “gu-lah-di-ant,” because no matter how you pronounce it, it just works. (As for science, if you pronounce it the wrong way, it sometimes may not work.)

“Statisticians get scared when optimizing more than ten parameters, but we fearless computer scientists optimize billions of parameters with gradient descent effortlessly.”

He even pronounces “honestly” with the “h” sound. “huh-nee-slee”. That’s because he doesn’t care how a posh French person would pronounce it (the word “honest” comes from Middle French). His way gets the meaning across.

If you strip his data from Siberian mammoths and send it through oil pipes, it could run Soviet tanks. His fearless methods work everywhere.

Part Four

With AI4Science, it seems like solving scientific problems needs less and less scientific knowledge, just more data.

AlphaFold only needs to read a sequence to predict protein structures. Disease screening only requires reading an image. Studying a specific discipline seems less worthy of one’s time than just making a huge dataset and feeding it into a neural network.

When I was young, naive, and curious about science, I took the Intro to Neuroscience class at MIT.

I ended up sleeping through every class and dropped it after two weeks. The only thing I remember is the professor saying, “I have a personal interest in bears.” because his last name was Bear.

When told him I would drop the class, Professor Bear said, “Young man, neuroscience is a long journey. There’s a lot of interesting stuff ahead. But like learning a language, you have to memorize the vocabulary and grammar first — what you’re learning now is just the most tedious part of the neuroscience language.”

Learning a language? I don’t have the time for that. Machine translation is quicker.

I swapped the class for a computer science class. Gotta stay away from the bear market.

Part Five

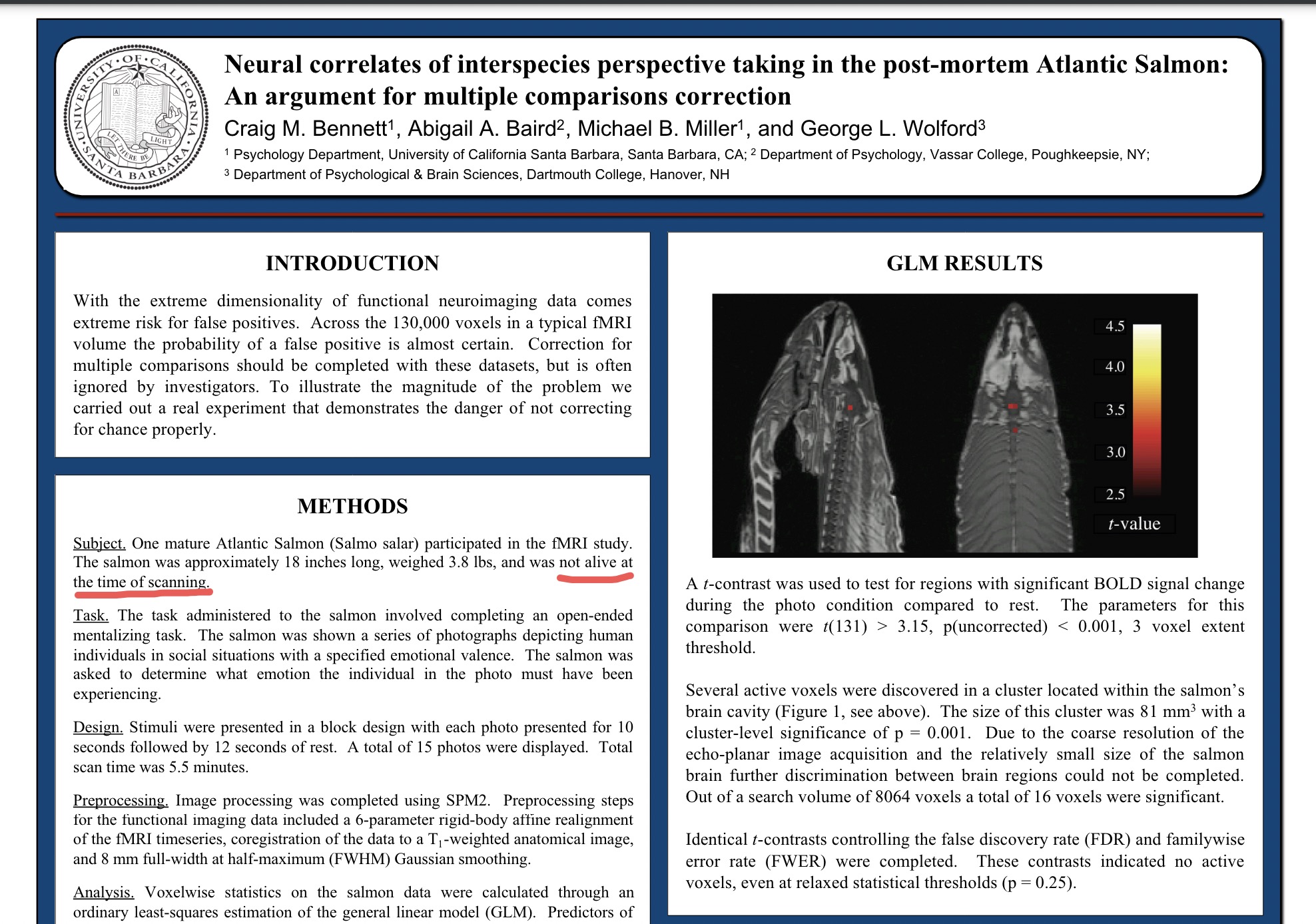

Professor Bear’s approach reflects the bottom-up thinking of neuroscience: starting small, studying neurotransmitters, neurons, neural pathways, and finally brain regions. This scientific rigor means every conclusion should be experimentally verifiable (well, should be).

However, this rigor is also a constraint.

Because many fundamental aspects are not fully understood, scientists are cautious about making fearless claims on issues people care about, like “how to learn more effectively” or “how to categorize people.”

This leads to a situation where fearless but unverified theories emerge before scientific evidence catches up.

Most people don’t have time to build a systematic understanding of neuroscience. They prefer simple, general theories like “left brain rational, right brain emotional,” “IQ above 140 means you’re in the top 1%,” or “the human brain has three parts: reptilian, mammalian, and rational.”

Despite academic disdain for these theories due to their inaccuracies, they become popular for their simplicity and applicability. IQ scores become entry criteria for some schools and companies; MBTI is what people actually ask about, not the Big Five; the three-part brain theory explains human desires and motivations and makes pop psychology bestsellers.

Traditional scientists, addicted to scientific rigor, dare not propose such fearless, universal theories. This violates their integrity as scientists.

“Pseudoscientists” don’t care. They step outside the existing theoretical framework, finding a balance between rigor and practicality, and propose bold theories.

They break free from the ivory tower, bringing fire to the world. This fire, though uncontrolled and potentially dangerous, also brings warmth and joy to those outside the tower.

Some may say with disdain that these pseudoscientists have never been inside the ivory tower in the first place.

Indeed, they have nothing to be afraid of because they have nothing to lose.

The world belongs to fearless people.

And I think the world is better with those pseudoscientific theories than without.

If the goal of science is to increase human understanding of the world, is verified, disease-curing science necessary closer to that goal than understandable, applicable pseudoscience?

Part Six

At one end of the world stands the ivory tower of academia, home to mathematicians, neuroscientists, and statisticians. They derive accurate theories with rigorous deductions and scientific methods. Their theories launch rockets, save lives, and build human knowledge.

At the other end is a bustling town where people are busy with their activities, having no time to ponder the symbols and theories on parchment in the ivory tower, but eager to live better lives.

In between walks a group of barefoot individuals traversing the knowledge wilderness. They carry stolen vases and torn pages from the ivory tower, looking to monetize them in the town.

They are unwelcome in the ivory tower, where they are called pseudoscientists.

But they bridge the ivory tower and the town.

There’s nothing shameful about being the bridge. Whether it’s the ivory tower, the town, or the barefoot individuals, all contribute to the world in their own way.

I want to be the bridge.

Part Seven

There has to be a way to prove that I am better. If the Big Five is not falsifiable, how is it science?”

I can’t do AI4Science because I lack hard science knowledge. But I know some psychology, so I can do AI4PseudoScience for my MEng (Master of Engineering) project.

To do AI4PseudoScience, we need to first identify the important problems in pseudoscience. I believe MBTI is one such problem.

It was devised by a mother-daughter duo after reading Jung’s theory. The testing method is primitive: self-administered questionnaires. Very unscientific. (btw, I’m an INTP)

I want to leverage machine learning to create a more accurate method of classifying people while keeping the simplicity and potential to become popular. Specifically, using representation learning to let machines summarize four new dimensions, then cluster into sixteen types.

Neural networks can do more than just read questionnaires. They can analyze videos, audio, text, and even mouse-click speeds. The test begins the moment you visit the website.

I combine machine learning and psychology, two important pseudoscience fields. Very cool. Very fearless.

I have a dream that one day people will ask about each other’s ANDI instead of MBTI.

When I brought this up to a neuroscientist, he said:

“However, let’s say, if you succeed and come up with your ANDI, how do you prove to the academia that it is better than existing personality theories, like MBTI or the Big Five?”

“Maybe I use ANDI to predict recruiting outcomes and social compatibility, and finds that it predicts better than the Big Five?”

The neuroscientist shook his head. “The Big Five researchers will say the Big Five is just a theory of personality. They never claimed it to be the best for predicting recruiting or social compatibility.”

“There has to be a way to prove that I am better. If the Big Five is not falsifiable, how is it science?”

He smiled. “Exactly.”

I was a bit frustrated, but then it dawned on me. I am not even working towards a PhD. I am just working towards a Master of Engineering degree. So, I don’t have to care about my academic future. What I care about is making personality theories better.

The Big Five researchers don’t have to acknowledge my work. Even if the whole academia doesn’t acknowledge my work, so be it. My work is for the laypeople who want to have a better understanding of themselves and each others.

I’ll be cool. I’ll Be fearless. I’ll make myself proud.